When notorious US bank robber Willie Sutton was asked why he repeatedly robbed banks, he allegedly replied “That’s where the money is”. This quip gave us Sutton’s Law, which states that when analysing a problem, one should first consider the most obvious, or likely solution.

Sutton’s Law can help investors to focus on the obvious facts and not become distracted by irrelevant details or unlikely scenarios.

It is important for investors to differentiate between what they know, but also to think about the consequences of what they don’t know. In our experience, this means focusing on fundamentals, rather than timing. A good starting point is to find where the money is.

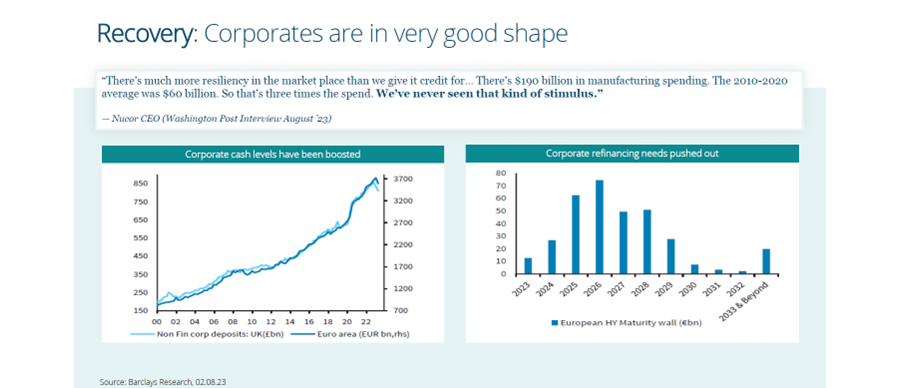

One healthy dynamic has been the rise in corporate cash balances. Businesses, conserved cash through the Covid pandemic to ensure their survival. They also used attractive lending rates to term out their debt. As a result, businesses are frequently enjoying the benefit of higher short-term interest rates on their cash, while their borrowings are still secured at attractive levels.

Now that we have found the loot, the investor should be concerned how, or if it will be used and how this might impact returns. Some will be used to pay dividends and special dividends, share buy-backs and acquisitions but we are confident that an increasing proportion will find its way into capital expenditure.

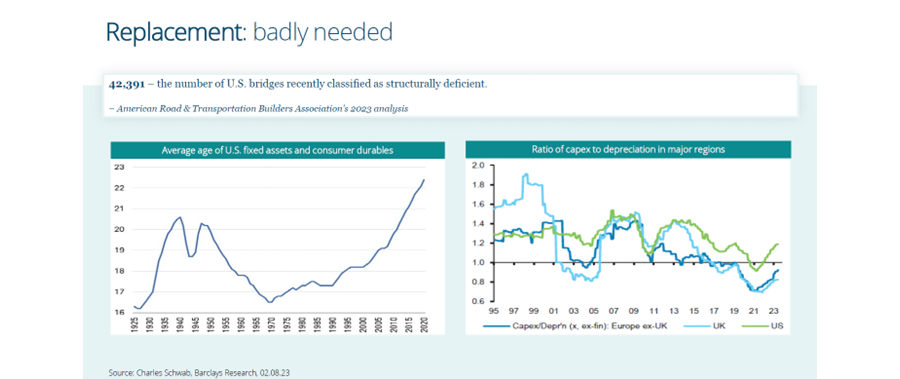

There has been underinvestment in infrastructure spending for the past 50 years. We have seen this in our electricity grid, water supply, roads, bridges, NHS and schools. However, it is not just infrastructure where there has been underspending; in many businesses, capex has been lagging depreciation.

Most businesses conserved cash through the uncertainty of the Covid period. They now face challenges such as improving supply chains by near-shoring, reducing energy consumption, waste and emissions. There are huge benefits from combining the potential of software with hardware to improve operational efficiency and resilience, in addition to the requirement to automate to replace labour shortages.

Let’s look at a few examples and we can see where corporate cash is being used to invest in the business and accelerate growth.

Heidelberg Materials is one of the world’s largest cement producers. While cement has many cost attractions and is suitable for large construction and infrastructure projects, the process is a large producer of carbon dioxide (CO2).

This is an unwelcome greenhouse gas and businesses have to purchase carbon permits to offset. However, for the more-farsighted business with the financial strength and ability to invest in technology, it also provides opportunities.

Heidelberg has been reducing the clinker content of its’s cement for at least the past six years, increasing the use of alternative fuel, such as biofuels and, as a result, reducing its specific CO2 emissions. Next year it will open the world’s first large scale factory for carbon capture in the cement industry. It will take around 400kt of CO2 from production and store it underground below the North Sea.

As a result, Heidelberg will have the competitive advantage of having to buy fewer carbon permits than competitors, but will also be able to sell the low carbon or zero carbon cement at a premium. Heidelberg has been able to fund this investment whilst also reducing group debt, completing a €1bn share buy-back programme and increasing the dividend.

Another example is Caterpillar, the leader in construction and mining equipment. To stay competitive, Caterpillar’s clients have to invest in new vehicles and the company offers many value adds that make the return on new investments worthwhile.

This starts with self-driving trucks, which help miners to cope with labour shortages. Another area Caterpillar has invested heavily in and stands out from the competition is electrical vehicles, which can be deployed in smaller mines, industries or road working.

These products help clients to reduce their emissions and improve their environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings. Caterpillar in turn can demand a premium for its products, which has come through in strong pricing power in the past couple of years.

American machinery company John Deere is also reaping the benefit of years of investment in research and development. The company spends around 4-5% of sales on innovation, which stretches from self-driving vehicles and interconnected tractors to soil and data analysis to help farmers increase their yield while reducing the use of pesticides and fertilizers.

By 2030 the company is looking to generate 10% of sales from recurring revenue such as software services. These services are higher margin and less cyclical than just selling hardware. But we don’t have to wait another seven years to see this coming through in numbers.

During the next downturn Deere expects to post trough margins twice the level of previous troughs, meaning the profits become less volatile. This should also result in higher valuation for the company’s shares.

This is where the money is: businesses that have the motivation to invest to survive and improve their competitive position. The evidence that this has started is overwhelming.

To catch-up on previous underspend and invest in new technologies is at least a decade long opportunity. If Willie Sutton was here today, I’m sure he would have spotted it.

Graham Campbell is senior investment director at River Global Investors and portfolio manager of the WS Saracen Global Income and Growth fund. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.