Most trusts investing in UK small-caps are too large to truly invest in the asset class, according to Rockwood Strategic manager Richard Staveley.

Portfolios with a high volume of assets under management (AUM) are limited on how small they can invest, which doesn’t give investors true exposure to the asset class.

Despite smaller companies being one of the largest investment areas in the UK, Staveley pointed out that the largest trusts in the sector share many of the same top 10 holdings.

Indeed, the five biggest IT UK Smaller Companies trusts – Aberforth Smaller Companies, BlackRock Smaller Companies, Throgmorton, Henderson Smaller Companies and abrdn UK Smaller Companies Growth – have similar names at the top end of their portfolios.

Stocks such as Gamma Communications, 4imprint, CVS, YouGov, Oxford Instruments, Watches of Switzerland and Vesuvius appear across multiple of their top 10 holdings.

Staveley said: “There's quite a lot of crossover of quite big companies that are technically called smaller companies that everyone owns, but no one owns our stocks.

“Our portfolio is a lot more higgledy-piggledy and as a result we end up with different outcomes than most small-cap managers.”

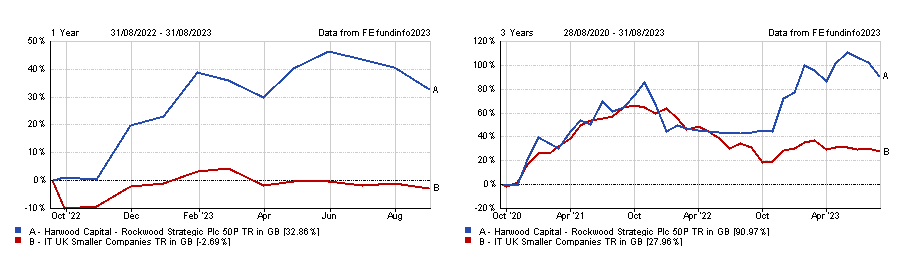

Indeed, Staveley’s total return of 32.9% over the past year was significantly higher than the 2.7% loss reported by the peer group, which he partially attributes to the trust’s small size. Rockwood Strategic has an AUM of £46m, which is four times smaller than the £184.2 average across the sector.

It was also the best performing UK smaller companies fund over three years to the end of August, with its total return of 91%, despite that time period being infamously challenging for small-cap investors.

Total return of trust vs sector over the past year and three years

Source: FE Analytics

Staveley said: “There is a structural reason why small funds often do a lot better than larger funds and if you actually think about it, most of the big problems in the industry come about when people have too much money to look after.”

Being small allows him to invest in tiny companies where he can have a lot of influence. Stakes in each company range between 5% to 29.9%, ensuring he has power to steer decision making.

“We've got more of a stake so we can say what needs changing and they know we can start making life a bit more difficult for them because we are meaningful shareholders,” Staveley added.

He himself is a non-executive director of two companies in the portfolio and the team has some form of board representation on most others.

One example where his large stakeholding influenced change was Crestchic, which was taken over earlier this year and boosted Rockwood Strategic’s returns.

A member of the team was on the board, which allowed them to replace the chief executive and get the company to sell one of its divisions, which ultimately made it more attractive to private equity buyers.

“We then took the money we got from selling that division and invested it into the remaining division and profits grew materially,” Staveley explained.

“In the end, a company called Aggreko bought Crestchic in February and we made 4.8 times on our money on that investment.”

He has seen a growing number of acquisitions in the small-cap space over recent years as UK investors divest from their home market.

This withdrawal of money from UK equities has left them underpriced, allowing private equity firms to swoop in and buy them at bargain valuations.

Staveley said: “UK investors are having this great migration to global equities and have been for a number of years and, if you've watched nature programmes, you’ll know that when great swathes of wilder beasts move away, the smaller ones left behind are eaten by hyenas.

“That would be the private equity guys who find these companies that have been left behind after all the domestic investors have run off to global equities, but there are actually some very nice plump businesses that are now being taken out.”

Rockwood Strategic’s small size may have been helpful, but another key differentiator is the trust’s value approach in a growth-dominated sector.

“It has become a minority sport in the UK and part of that is because the style is linked to the value of cash flows. The environment we've been in since the manipulation of monetary policy after the great financial crisis over 10 years ago has undermined the theory because there was no value from cash. That backdrop allowed valuation to be less important to investors than it should be.”

This may be one of the key reasons why larger names in the sector are so concentrated. Staveley said these firms share the same growth bias, which leads them to the same names.

The only exception is Aberforth Smaller Companies, which is also in the minority of small-cap investors buying through a value lens.

“Outside of Aberforth, most fund managers will reference valuation, but it won't be their number priority,” Staveley said.

“They'll talk about quality businesses or growth businesses, but they won't consider first and foremost whether the thing is trading for less than it's worth. They often think of valuation in a relative sense because they're trying to beat a benchmark.”