Performance fees – perhaps there is no more controversial two words in the investment lexicon. The charge, which is applied on top of the regular expenses included in the ongoing charges figure when a portfolio outperforms select measures, has both its fans and critics.

Many investment companies have shed their performance fees to compete with their open-ended cousins, according to Annabel Brodie-Smith, communications director of the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), but 92 trusts still have them, 39 of which are invested primarily in equities.

Three trusts abolished their performance fees in 2022, but many investment companies have kept their charges in place, each with its own performance fee and hurdle that the trust must pass for the additional fee to be charged, but the details differ from trust to trust.

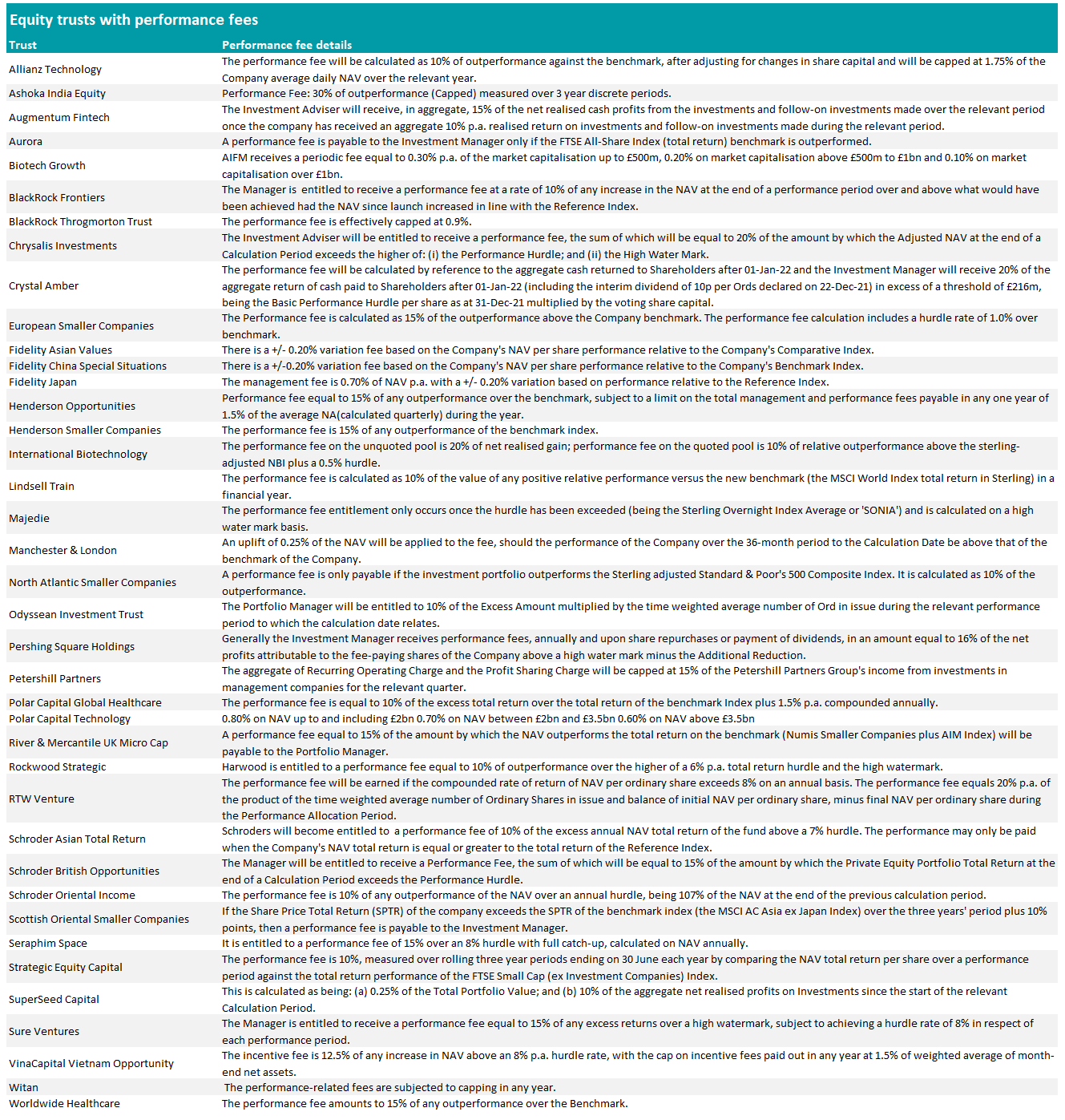

The table below lists the equity trusts with performance fees and the details they provide on their charges.

Brodie-Smith advised investors to “look at the performance fees and make sure that they’re happy with them, just in the same way that investment companies need to make sure that they're communicating what that fee is and helping investors understand”.

She pointed out that trusts in specialist sectors are more likely to maintain a performance fee, with more than half (57.6%) of trusts with these fees invested in alternative assets.

“You've got to think about an investment company attracting a manager in a specialist sector that's very competitive,” Brodie-Smith added.

The AIC offers guidance for trusts using performance fees in its Code of Corporate Governance, which states they should use appropriate benchmarks, hurdles and fee caps.

However, the performance fees on many trusts are still structured poorly, according to Jock Glover, strategic relations director at Square Mile Investment Consulting and Research.

He said: “The trouble with performance fees is that invariably they're structured badly. They’re becoming increasingly difficult to justify in the world we live in now.”

Glover highlighted that some investment companies set their hurdles too low, which makes it easy for them to surpass their goal and charge a performance fee.

Likewise, investors can still be charged a performance fee even if returns are down so long as the fund beats its benchmark index.

These are the two main issues Glover encounters with trusts charging performance fees, but they would not necessarily deter him from investing in those portfolio, as a trust should be judged first and foremost on its performance and consistency in delivering its objectives.

Performance fees can be inconvenient for those that wish to plan their costs, however as they make it impossible to work out the future cost of holding a trust in their portfolio as outperformance could add extra expenses to their bill.

Glover said that this is particularly frustrating for advisors, who often avoid trusts with performance fees as they can’t give their client a clear idea of charges.

He added that if a trust outperforms and charges a fee, “you might as well have bought a tracker once you take into account all the fees” in some instances.

One of the main purposes of a performance fee is to align managers with their trust and its shareholders, but this claim is flawed, according to Glover.

“If you're being paid 75 basis points of assets as a fund manager on a portfolio worth a few million pounds, that ought to be enough of an incentive for you to do your job,” he said.

A performance fee wouldn’t discourage Glover from selecting a fund that is otherwise strong, nor does he think managers shouldn’t be rewarded for good performance, but he did say that there are better ways than charging shareholders.

“If you're doing a good job, your assets ought to rise because your performance is good. You shouldn't need that performance fee to increase your assets and therefore your revenues,” he said.

Source: The Association of Investment Companies