In recent years, a string of unusual developments has caused UK equities to become one of the least popular items on the investment menu. But something is happening to make them much more appealing. Unnoticed by capital markets, companies are deploying their surplus cashflows to buy a dish that is both cheap and familiar: their own shares.

In short, UK companies are eating themselves. And this is not a light starter, but rather a hefty main course with all the trimmings. These share buybacks are happening on a scale we have never seen before.

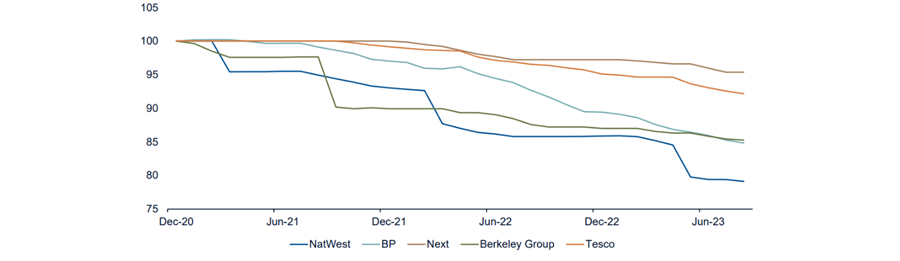

Share counts of some UK companies have shrunk dramatically in recent years

Source: Bloomberg, Artemis as at 20 September 2023. (Share counts rebased as at 31 December 2020).

Many investors treat share buybacks with scepticism. This is understandable if valuations are high. And if managers are focused on driving short-term momentum in earnings per share at the expense of reinvesting in the business to create long-term value for shareholders. That is not what is happening here.

A significant number, having reinvested to sustain and enhance competitive positioning, are looking at the compelling returns available from reducing their share count and simply saying: ‘If you won’t buy our shares at this price, we will.’

Share buybacks work best when a company’s shares are cheap relative to its earnings. And this is precisely what we see today. The UK stock market is on sale. It trades at one of its lowest-ever valuations relative to both its own history and other stockmarkets around the world. Put simply, by buying back shares, companies are purchasing their own cashflows at a very attractive price.

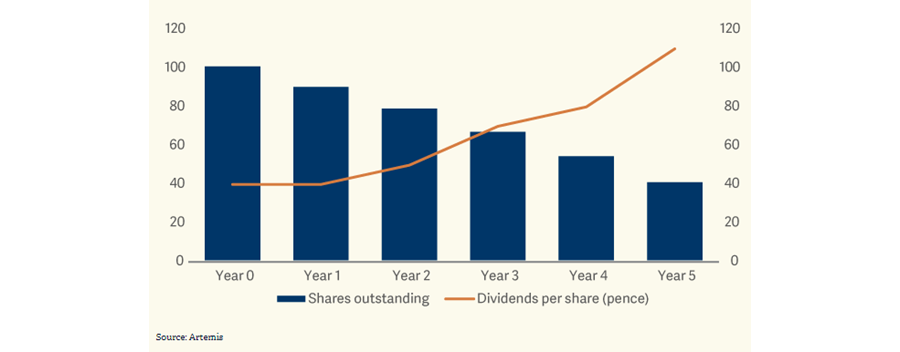

It is worth looking at the maths to see the potential impact. Consider ‘Good Co’, an imaginary company with 100 shares in issue and £100 of net income, which generates £1 of earnings per share (£100/100 shares). With investment largely going through its profit and loss, Good Co pays out 40% of its net income in dividends and 60% in share buybacks. It grows its net income at 6% a year.

Despite reinvesting to ensure that its future is sustainable, Good Co is unpopular with investors: it trades at price-to-earnings multiple of just 6x, giving a share price of £6 and a total market cap of £600.

Good Co’s low starting valuation means that, in year one, £64 of share buybacks reduce its share count by 11%. Thereafter, as it directs 60% of its net income to share buybacks each year, a powerful form of ‘reverse compounding’ occurs. In year two, buybacks reduce Good Co’s share count by 13%; in year three by another 15%; and in year four by 19%. In year five, 25% of its shares are retired.

‘Reverse compounding’ in action- as Good Co buys back shares, dividends per share increase exponentially

By the end of this process, Good Co’s share count is 60% lower and its dividend per share has increased by 185%. For its patient shareholders, that means that what started as a generous 7% dividend yield has compounded to a whopping 19%.

If it keeps going, Good Co will have reverse-compounded its way to the ‘golden share’ – the last remaining stock in the company – within eight years.

‘This cannot happen’, you shout. ‘Surely, Good Co’s share price must adjust upwards to reflect the fall in the number of shares in issue.’ But this highlights the most perplexing aspect of these share buybacks, which is how little impact they are currently having on share prices. If cashflows per share rise year-in, year-out, then surely share prices should too?

There is little evidence of this among the large brigade of UK companies that have been buying back shares for a couple of years now. BP has reduced its share count by 16% in just over 18 months. NatWest has reduced its share count by 22% in less than two years. Since late 2016, property developer Berkeley Group has reduced its share count by 30% from 150 million to 105 million.

These are far from isolated incidents; in the past 12 months, some 57% of our portfolio by value has bought back shares.

Do we really expect to be the last remaining shareholder in BP? Or in NatWest? Clearly not. But the most likely reason that won’t happen is that the share prices of these companies move up – significantly – when the world takes notice. The increase in demand for the shares will then be met with a rise in the share price.

Can UK companies really continue to grow cashflows and buy back shares?

Some may argue that the UK economy is not in great shape and so the prospect of these companies continuing to generate surplus cashflows is questionable.

Yet while this has been the dominant narrative since Brexit, it has not been borne out by reality. Not only has the UK outperformed Germany and France on a GDP basis since Brexit was finalised in late 2019, but 75% of the FTSE 100’s revenue comes from outside the UK.

Stockmarkets are discounting mechanisms and, although they should be logical, emotions and misleading narratives mean that logic often breaks down. This presents an opportunity. The UK has a wealth of well-run, profitable companies with strong balance sheets and global opportunities. But they are currently being priced like they are challenged UK domestic businesses.

Take Next, for example. It is viewed as a challenged UK high street retailer, but it generates 65% of its revenue digitally and has overseas growth opportunities for its popular core brand and for recently acquired businesses such as Reiss, Fat Face and Joules.

Or look at Tesco, whose 4% dividend yield is growing at 5% from share buybacks alone, and which has more market share online than offline. Tesco Whoosh operates out of more than 1,400 sites, offering rapid delivery services to more than 60% of the UK population. This is hearty fare for patient shareholders who have seen their share of profits grow without having to lift a finger or spend a penny.

In our minds, this all adds up to making the UK stockmarket one of the most interesting items on the global investment menu. For now, prospective buyers have yet to be tempted. But as time goes on, and they begin to notice the beneficial compounding effect that significant buybacks have on a cheap market, we believe that will change.

Fortunately, investors in equity income strategies are being paid to wait for that change – and paid handsomely given the dividend yields on offer these days. Reinvesting those dividends multiplies the impact of share buybacks and intensifies the effect of compounding.

While most investors have, unlike the companies themselves, yet to regain their taste for buying UK equities, we believe they could soon become the dish of the day.

Nick Shenton is co-manager of the Artemis Income fund. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.