Gilts are offering an attractive yield for the first time in a long while, but after years of disappointing returns, fund managers have mixed views on the asset class.

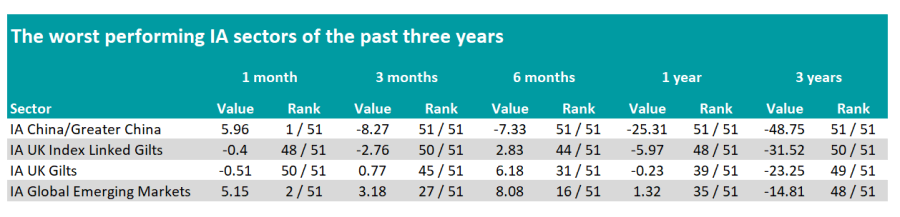

Gilts were the worst performing asset class for the past decade, the second worst over five years and within the bottom three for three years, judging by the relative performance of the Investment Association (IA’s) sectors. Only index-linked gilts and the IA China/Greater China sector lost more money in the past three years.

The average gilt fund fell 23% over three years, but most of those losses were incurred in 2022 due to aggressive rate hikes and the disastrous mini-Budget that September. Gilts have clawed back some ground in the past 12 months, when their performance ranked 39th out of the IA’s 51 sectors.

However, with yields in excess of 4% now on offer (10-year gilts were yielding 4.14% as of 22 February 2024) investors might be ready to take a fresh look at UK government bonds.

Indeed, Mike Riddell, manager of Allianz Index-Linked Gilt,is so bullish on gilts they are his favourite government bond market. However, Paul Skinner, investment director at Wellington Management, warns that gilts are not offering a high enough yield to compensate for the risk.

Source: FE Analytics

The bear

Skinner is concerned about persistent inflation and about the UK’s overreliance on foreign investment; he does not believe that gilts are compensating investors sufficiently for these risks.

“I am bearish on gilts. I feel the UK should probably be paying a little bit more for its borrowings, because, fundamentally, we have a much more embedded inflation issue than many other countries,” he said.

“We have a technical indication of a trading range of 3.5% to 4.75% on the 10-year Gilt, so even though we don’t make point forecasts, gilt yields could be 60-75bps higher if the market turns less enthusiastic on rate cuts because of stickier inflation.”

One of the reasons why Skinner believes UK inflation could be stickier than expected is down to persistent demand for labour. While this is also true in other countries, he noted that the UK has high levels of wage agreement and has been dealing with strikes in recent years.

Another reason for his bearishness is due to the UK’s reliance on foreign investment to finance its debt. Therefore, the UK is particularly sensitive to flows from international investors, in contrast to countries such as Japan, which despite being a “massive” borrower, benefits from a large domestic savings base that can support its debt.

Skinner said: “If you're looking at places where there's a focus on things such as: ‘is the money flowing in or is it flowing out?’, ‘Has the government got the right balance on how much they're borrowing?’, etc., the UK is quite a good poster child.”

Finally, he pointed to the mini-budget of September 2022, which shocked markets. It caused a dramatic surge in gilt yields – which are inversely correlated with prices – and sent the pound sterling crashing.

Skinner said: “If you look at developed markets, one that's flirted with danger recently is the UK. Truss’ mini-budget was all about testing the limits of bond markets to finance government spending above and beyond what is normal.”

The balanced view

Miles Tym, manager of M&G Gilt & Fixed Interest Income and M&G Index-Linked Bond, is not as bearish as Skinner on gilts, although neither is he champing at the bit to buy them.

While Tym acknowledged that the term premium – the additional yield that investors require for bearing the risk of holding longer-duration securities – may be trending higher, he stressed that there are many moving parts to gilt valuations.

Tym said: “If interest rates come down, then even with rising term premiums, it is perfectly possible for gilt yields to fall overall. In effect, if administered base rates fall by say 1.5%, and gilt yields fall by only 1%, the term premium will have increased, but gilts will still have rallied in price terms.”

He also questioned whether the UK has a “meaningfully worse” inflation problem than other countries. While the spike in inflation over the past two years was higher in the UK, Tym stressed it is difficult to determine how much of it is structural and how much is cyclical.

“With the benefit of hindsight, the massive monetary easing in response to Covid was a mistake, but in the five years prior to that (2015-2020), UK CPI inflation averaged only 1.7%, actually below the Bank of England’s target. We would not be that surprised by an inflation undershoot within the next 12-18 months,” he explained.

While he acknowledged that foreign buyers are a significant force in the UK gilt market, Tym does not find it as concerning as Skinner does, as he noted that flows did not dry up in 2022 and 2023 as inflation spiked dramatically higher.

Tym said: “We would not suggest that the UK should be complacent about how permanent these flows might be, but if a big spike in inflation did not scare them away over the past two years, it may be a bit pessimistic to fear that slightly sticky inflation may do so this year.

“Net foreign buying of gilts has been very close to £40bn in each of the past two years. [International investors] were scared away during the turbulence of late 2022, when they feared the entire fiscal framework had been abandoned, but rapidly returned when the administration changed. So long as any UK administration remains committed to a fiscal framework, we do not see international investors taking flight from the gilt market.”

The bull

In contrast to Skinner’s bearishness and Tym’s neutrality, Mike Riddell, manager of Allianz Index-Linked Gilt, is bullish on gilts, which are his “favoured government bond market globally”.

In recent times, his preference has shifted toward the longer maturity part of the gilt market.

He explained: “The UK gilt yield curve has substantially steepened, partly on fears of Conservative party giveaways ahead of the next general election, but these fears looked fully priced in to us. Valuations now seem very cheap, where the yield on a 30-year gilt is 4.5%, and has barely ever gone above 5% in the last quarter of a century.”

Finally, Laith Khalaf, head of investment analysis at AJ Bell, reflected that although gilts have been a disappointment for a decade, their prospects look better now than at any point since the financial crisis.

“The good news for gilt investors is that prices have reset to much more reasonable levels and yields look relatively attractive. There are still risks out there, notably sticky inflation, the UK election, and the potential for a supply glut coming from a combination of Quantitative Tightening and new issuance,” he said.

“However, the risks and returns on offer look far more balanced than they have since the financial crisis.”