We have all been there. It’s 3am and you have to get up to go to the airport because you bought the cheapest early flight from the farthest airport and now you are regretting it and thinking: Was that really worth it?

Investors should be asking themselves the same question when they are paying an active manager who is only active in name, said Barry Norris, who runs the £154.8m Argonaut Absolute Return fund.

“The current regulatory environment is pushing everybody to take the six o'clock Ryanair flight from Stansted,” he said. “It might be cheap, but we'll have different opinions about whether that constitutes good value.”

To him, the investment equivalent of getting to the airport comfortably is alpha, or the measure of the gains that the manager could make on top of the underlying index’ growth (beta); and the equivalent of not having to get up at the crack of dawn is the correlation to the index, which should be as low as possible.

Too many managers are too correlated with their index and charging “alpha” fees for “beta” performance, and therefore classify as the low-cost airlines of asset management.

“Managers who sell beta with an active management fee, or even a performance fee, are vulnerable to be out of business – they should be out of business. If a fund has high correlation to its index, buyers should question why they couldn’t buy that beta more cheaply,” said Norris.

“If active management is going to survive, it needs to be a case of why you pay more for active management versus passive, because active is never going to compete with passive on costs.”

Instead, by comparing their own performance against that of an index, active managers are effectively taking on the competition with passive funds, which is “just too high” because they are inherently cheaper to run.

“If you’re only trying to add alpha in excess of the index, investors can always buy the index less expensively,” said the manager.

On top of that, strategies that charge an extra fee to beat a benchmark are also always going to be more inconsistent than that index – yet another disadvantage for buyers, who also need to put up with a widespread uniformity and lack of diversification in the relative-performance industry.

“Over the past decade, what’s worked well is being long on tech and the US, and too many people were pushed to own the same things”, he continued.

“A minority of investors get this, but the reason they should pay an active management fee or performance fee should be to get a return profile which you can't replicate more cheaply.”

In the case of Argonaut Absolute Return, that means looking to achieve an absolute return instead of a relative- return, and having a short book as well as a long book, which generates an “uncorrelated and diversified” return profile.

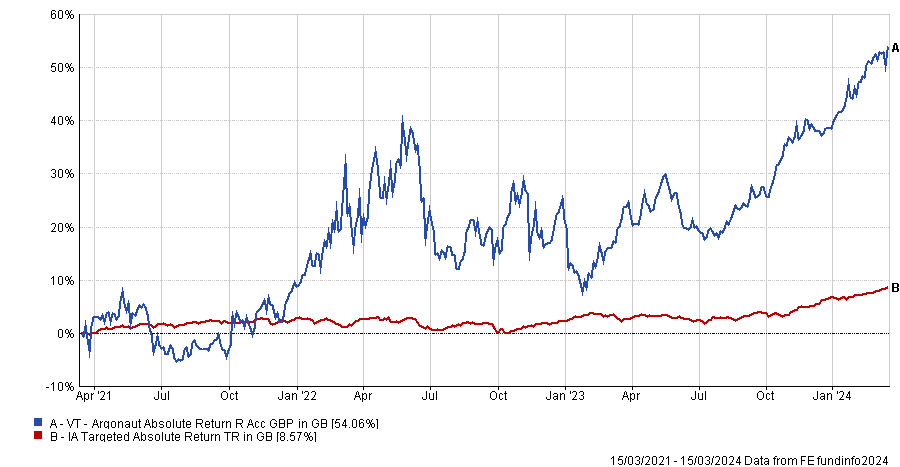

The strategy aims to deliver positive returns over three years, regardless of market conditions, which, for the manager, should be enough to convince investors to fork out some extra money for the benefits it gives.

Performance of fund against sector and index over 3yr

Source: FE Analytics

And Norris’ fund does charge more – its ongoing charge figure (OCF) is 0.90%, on top of which investors pay a 20% performance fee that kicks in after hitting a performance hurdle of 5% per annum, which the manager isn’t planning on changing.

“When interest rates were zero, all our competitors had Libor [the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate] as their hurdle rate, so they were charging zero and we were charging five. Now that interest rates are five, we're charging five and all our competitors are still charging zero.”

“Also, businesses like ours wouldn’t exist without a performance fee. With a simple management fee, we would be like the rest of the industry that gets paid on the amount of money that they run and we'd be solely focused on managing a bigger fund, rather than a better fund,” he concluded.