The announcement of broad US tariffs on Canada, China, and Mexico, along with the market reaction, highlights the potential disruption to the global economy and financial markets from president Donald Trump’s trade policy.

While economic constraints may ultimately limit the president's proposals, uncertainty surrounds the future of US trade policy. The inflation risks are concerning, and investors using the 2018-2019 trade war as a guide could be caught off guard.

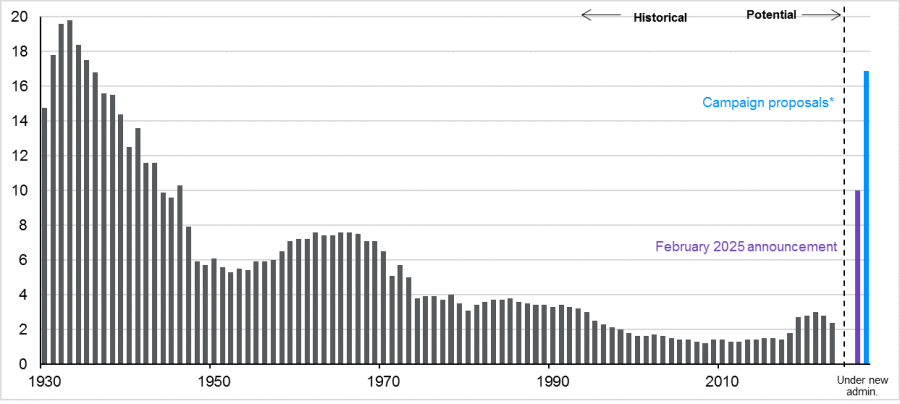

The policies announced at the start of February would have quadrupled the US tariff rate from 2.4% to 10%, still below the 60% on Chinese imports and 20% universal tariff Trump promised. These would raise the effective tariff rate on US imports still further to 17%.

The different economic situation this time may eventually constrain the president but the larger-than-expected size and scope of February’s initial announcement increase the risk that politics overrules economics and high tariffs remain a more permanent feature of US trade policy.

Average tariff rate on US goods imports. Duties collected / value of total imports

Source: Cato Institute, U.S. Department of Commerce, various news outlets, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Includes all current official revisions for 2010-2020 as of July 2021. *Estimate is by JP Morgan Asset Management. Potential tariff rate assumes: 60% tariff on all imports from China, 20% universal tariff, 0% tariff for goods imported under Free Trade Agreements. Data as of 3 February 2025.

Four reasons why history may be a poor guide to the future

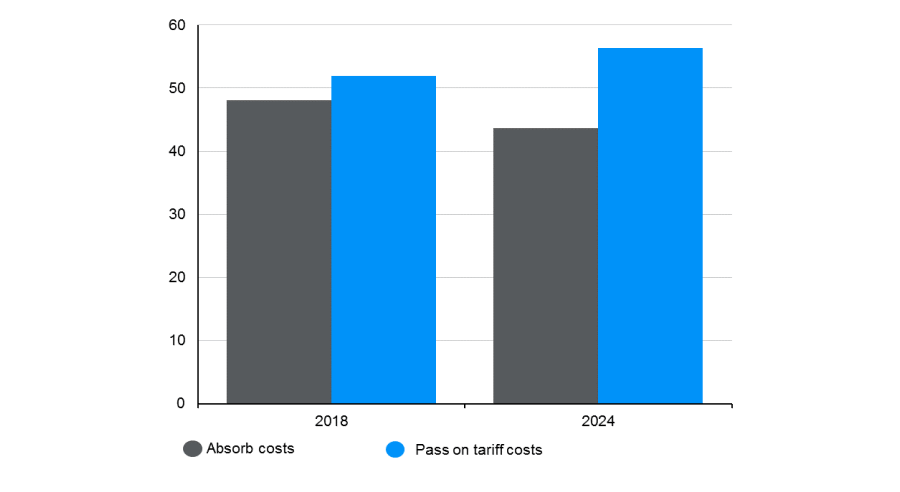

In 2018, targeted tariffs on Chinese goods had a muted effect on inflation due to their narrow scope. The broader 2025 proposals could have a larger inflationary impact, with fewer loopholes to offset price pressures and corporates more willing to pass on costs.

First, while overall inflation remained contained in 2018, tariff-exposed sectors saw upward pressure on prices. Major appliances, such as refrigerators and washing machines, which had seen consistent deflation over the previous five years, saw prices rise by 10%, and a similar story played out across other tariffed sectors.

However, the targeted nature of the 2018 measures meant that the overall inflationary impulse was contained. This time, a far greater swathe of imports could be captured, risking a greater inflationary impact.

Second, in 2018 the devaluation of the renminbi was a major offsetting factor for the competitiveness of Chinese exports. Between April and October 2018, the Chinese currency fell 10% against the US dollar.

But currency devaluation is unlikely to be as effective as a countermeasure to US tariffs this time. The real effective exchange rate of the US dollar is at its highest level since 1985, and the US administration is explicitly looking at currency manipulators as targets for tariffs. Attempting the same devaluation policy could risk compounding the problem.

Third, rerouting trade to avoid tariffs could prove harder in 2025. The longer-term impact of the 2018 tariffs was offset by changing supply chains. China’s share of US imports has fallen since 2018, benefitting countries like Mexico and Vietnam.

However, import data from these countries suggests a significant proportion of this increase could be accounted for by transhipped Chinese goods. The administration’s recognition of this phenomenon, as well as the broader range of countries being targeted for tariffs, means there is less scope for this to happen again in 2025.

Finally, corporations appear more willing to pass on tariff costs to end consumers than in 2018. This shift is reflected in recent earnings calls.

Corporate plans to respond to tariffs. Percentage of corporate earnings calls discussing plans for tariff costs

Source: Bloomberg, JP Morgan Asset Management Quantitative Research. Data derived from 2018 and 2024 earnings call question and answer sessions where a clear plan to dealing with tariff costs was explained. Data as of 3 February 2025.

How should investors position portfolios?

Given these factors, there is a risk that Trump’s tariff policy in 2025 is more inflationary than in 2018. The scale and duration of US tariffs and trading partner retaliation will be the key variables that dictate the size of the inflation impulse and growth hit.

Ultimately, we see tariffs as a tool to incentivise new deals. The new administration inherited a booming stock market and a mandate from the voters to fight inflation, both of which could be at risk if the tariff card is overplayed.

If large tariffs lead to significant economic and market volatility, the US administration could feel pressure to declare victory on a number of political issues, allowing president Trump to reduce tariff rates. If this is the case, then price pressures should be short-lived and risk-taking should still be rewarded in the medium term.

However, investors should beware that the inflationary risks inherent in an aggressive trade policy could turn out to be an unpleasant backdrop for markets.

Portfolio diversification will be key, and while government bonds remain important in case business sentiment sours, investors should also look to bolster allocations to inflation-protecting assets, many of which can be found in private markets.

Max McKechnie is a global market strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.