The number of US stocks that have outperformed the S&P 500 on a 12-month view is the lowest it has been in a quarter of a century. The index is up nearly 18% this year, but most of that is coming from a handful of giant tech stocks.

Apple (up nearly 50% this year) is now worth more than the market cap of all the Russell 2000 small-cap companies put together. It represents nearly 7.5% of the S&P 500; Microsoft (up 50% this year) represents nearly 7%.

It is easy to forget that only last year, as interest rates soared, investors decided valuations of these stocks were too rich and scrambled for the doors. What has changed since to cause this sellers’ remorse? Have interest rates gone down dramatically? No. Do they look like they will soon? I do not think so. Are sales up? Apple and Microsoft toplines (for now at least) are growing less than inflation.

These companies are valued as if they are returning to the levels of growth they enjoyed in the decade up to 2021. But there is a big difference between paying 25 times earnings for Microsoft’s shares in an environment of zero interest rates when the company’s top-line growth was 15% a year and doing that now.

Complaining about the remarkable performance of these shares sounds like sour grapes. As the old saying goes: ‘A bubble is when something you don’t own goes up every day’. But markets have been tough for active managers this year and for income managers in particular.

Few sensible active managers will have more than 5% in one stock, so they will be underweight Apple and Microsoft. They might be underweight other 2023 tech winners on valuation grounds. Nvidia’s shares are up 225% so far this year. Much of this is because of artificial intelligence (AI) excitement and expectations of continued soaring demand for the company’s chips.

As an income manager, I preclude myself from investing in Apple, Microsoft or Nvidia, because they pay less than 1% yield. In fact, 80% of active returns this year in the MSCI ACWI have been driven by stocks that yield less than 1% or nothing.

So after a good 2021 and 2022 – when the tech stocks took a dramatic tumble – my fund is lagging in 2023. At least I am in good company. But what are markets telling us?

Flight to quality

Perhaps people are scared. The era of quantitative easing (QE) and zero interest rates has ended. What we are witnessing may be typical of the counter moves you often see at these points – a conflict between secular and cyclical trends.

Maybe you buy Microsoft and Apple shares on the assumption that you can sell these stocks again in a couple of months or years. They will “grow into their valuations” and in the meantime excess liquidity can sit in these apparently safe, high growth and super-liquid names.

That would make them the new government bonds – our new ‘safe place’. This makes sense to some degree. These are outstanding companies. The world runs on Microsoft and Apple and they have global quasi-monopolistic status.

Meanwhile, for many traditional income stocks yielding 3-4%, a risk-free rate in the short end of 3-4-5% has been a large headwind.

But caution is surely needed. These supranational tech companies are not countries and they cannot raise taxes. They are subject to regulation from governments that could curtail their monopolistic powers. They can be taxed, split, and regulated via nudging in the Oval Office.

The Nasdaq is re-balancing the index to give passive investors a more diversified experience and that must have an impact. Finally, no company is immune to disruptors even when we ask ourselves whether anything will ever make us leave the ecosystems.

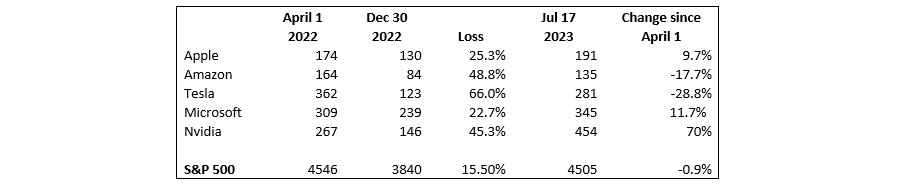

Recent history shows that the share prices of these companies can fall. Between April Fool’s Day and New Year’s Eve last year Apple, Microsoft, Tesla, Amazon and Nvidia lost 41.6% on average (against the S&P, which lost just 15.5%).

So far this year the same stocks have averaged a 106% rise. Remember, when you lose half your value you must double what is left to get back to where you were. It is interesting to look at prices rather than percentages over the past 15 months. Tesla and Amazon are still significantly down. It is Nvidia that stands out.

Source: Artemis

The world is changing. I am happy to stick to solid companies that make things we need (they can benefit from AI, too), that generate a dividend and that are attractively priced.

Yes, they are facing headwinds. But experience tells me that over the long run this is a safer, less volatile way of delivering returns. Over the past hundred years equities have delivered around 8% a year. If you can generate around 4% in dividends then you are halfway to achieving that return – and dividends are less volatile.

When I look at companies and their earnings I see European banks delivering upgrades, despite being out of favour. Stocks with exposure to copper mining, have had a share drop-off (Glencore down nearly 20% this year on the economic meltdown in China), but we will need more copper for all the electrification planned, whatever Chinese growth is.

I look at companies like Italian high-voltage cable manufacturer Prysmian in industries that have been commoditised. These are selling at low multiples, because they make things we think anyone can make and that for many years the Chinese have made more cheaply. But I think this thesis needs challenging.

Deglobalisation supports these companies. So do their scale and their quality of product. To compete will require huge investment – and, with interest rates higher, that becomes more expensive. Their barriers to entry have been rising without us noticing. We see value and upgrades in many other areas in our portfolio.

Undoubtedly the surprise this year has been the 1999-like rally in anything AI-related. We know, these things can run for a while, even when valuations are hard to justify. So one should be careful not to dismiss the rally for now. But if we go back to an environment where earnings and cashflow matter – and I believe we will – then the second half of the year could look very different to the first. I hope so.

Jacob de Tusch-Lec is co-manager of Artemis Global Income. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.