There is an easy way to fix the UK market’s woes but the government is unwilling to take the necessary action, according to Alec Cutler, manager of the Orbis Global Balanced fund.

The UK is filled with attractive businesses that have been left at bargain prices after years of outflows but, frustratingly for international investors, the government has made no effort to address this, the FE fundinfo Alpha manager said.

Foreign investors are attracted to the UK market but without a catalyst for change it risks falling off the international stage.

“Most investors who invested in the UK have been burned,” Cutler said. “Everyone has to go through their ‘I'm-going-to-buy-British-stocks’ period of pain before realising it's a bug zapper. That has led to an apathetic investor base.

“Brexit hurt and got a lot of people to take their eye off the UK. The level of dysfunction the government has experienced over the years since has also been tough. All that uncertainty just turns off a foreign investor.”

UK investors have removed £35.5bn from their home market over the past three years, according to the Investment Association. While that has led to attractive valuations, this is not enough in itself to tempt investors back.

Luckily, there is a solution on the table that could significantly change the UK’s fortunes, even if the government won’t seize it, Cutler said.

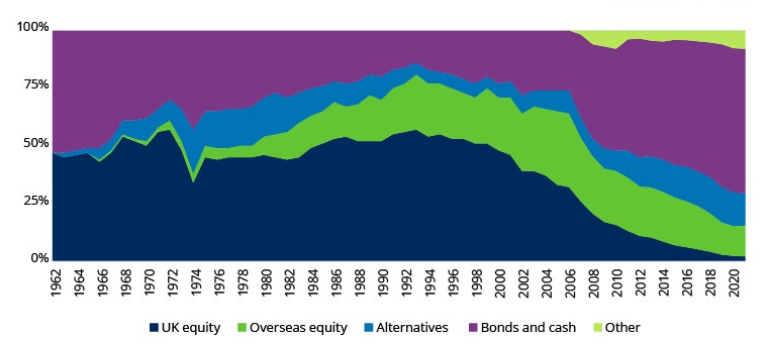

Most of the money leaving the UK is heading out through pension funds, so that is where the government needs to target, he argued. These massive funds used to hold more than 50% of their assets in UK equities in the 1990s, but now the home market accounts for less than 2% of assets.

Asset allocation of UK defined benefit pensions since 1962

Source: Schroders

At the turn of the century, the government intervened to encourage those pension funds to invest in fixed income to reduce risk – reversing that would be the most obvious catalyst to save UK equities, according to Cutler.

He said: “[Pensions] only changed because the government told them to, so why doesn't the government tell them not do that anymore, or at least something to equal the playing field for British companies? They've done it in other places.

“But no, they're just doing dumb things like trying to get pension plans to invest in venture capital, which doesn't fix anything – it makes it worse.”

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has been developing the idea of directing some of the money locked away in defined benefit pension funds towards private equity.

However, funnelling this money towards emerging smaller companies would be a “kick in the teeth” to other British companies. Cutler argued that supporting these businesses will create new competition while “screwing over the existing British company base”.

He added: “They’re telling existing companies that they’re going to give cheap funding to startups to compete with them – doesn't that just make things worse?

“And how long is it going to be before those companies that they're funding with cheap capital start listing? And who says they're even going to list in the UK? It’s just making the problem worse.”

Others have been critical of the chancellor’s idea, with Yvonne Braun, director of policy at the Association of British Insurers (ABI), warning the government to “exercise extreme caution”.

“Introducing these market-shifting proposals may bring significant risks for highly uncertain rewards,” she added. “Changes must not be rushed. Proposals must be thoroughly considered for the long-term and ensure that savers’ needs are at the heart of all pensions policy decisions.”

Similarly, Rob Yuille, assistant director at the firm, also cautioned the government to ditch this plan that could put consumers’ savings at risk.

“As it stands, the proposed solution isn’t workable,” he said. “We’d encourage the Department for Work and Pensions to press pause on developing this policy until the numerous challenges can be tackled.”

The chancellor’s current plan may be unfavourable, but Schroders head of strategic research Duncan Lamont said Cutler’s alternative wasn’t any better.

“UK pension funds are the popular and convenient whipping boys for a range of woes hampering Britain’s financial fortunes,” he said. “This is unfair and unhelpful.

“If something makes sense from an investment perspective they should and, in my experience, will consider it. But they are not piggy banks to be raided for whatever happens to be the political priority of the day. The suggestion that it could be reversed by a wave of a regulatory wand is misguided.”

Lamont argued that pension funds are an easy scapegoat for policy makers wanting to solve the UK’s outflow problem but they have done a better job at shielding investors’ savings by moving away from UK equities.

He pointed out that the five biggest companies in the UK make up 36% of the total market, with the largest 10 accounting for 53%. Withdrawing allocations from these stocks has made pension funds far less concentrated.

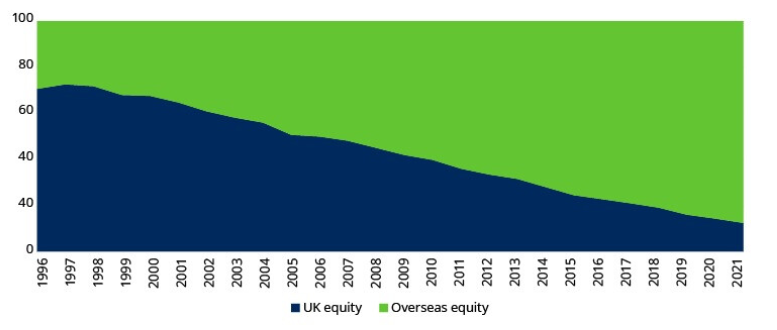

“The first big shift out of UK equities arose after defined benefit advisers and trustees sensibly decided that having quite so much of their equity portfolio in the UK wasn’t very diversified,” Lamont said. “This is especially the case given the UK itself has always been a top-heavy stock market.”

UK vs overseas equity exposure in defined benefit pension funds since 1996

Source: Schroders

Likewise, pension funds had barely any exposure to asset classes outside of equities or bonds 20 years ago – the addition of private equity, infrastructure, real estate and other alternative assets classes has gone another step further in improving diversification.

“Pension trustees’ efforts to build more diversified portfolios, both within and across asset classes, have been a major contributor to less money being allocated to UK equities,” Lamont said. “None of this was regulation-driven and most people would surely agree that diversification is a good thing.”