Investors in emerging markets have watched over the past few years as the region’s two largest markets have had wildly contrasting fortunes.

On the one hand, India has flown higher on the back of stability and sold economic fundamentals, while China has languished with concerns over government intervention and economic sluggishness.

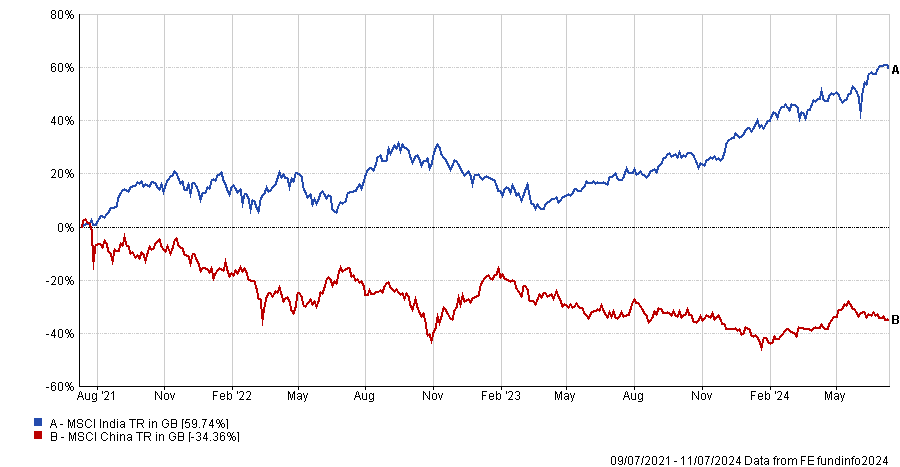

This has been borne out in the two stock markets, with the MSCI India up 59.7% over three years while the MSCI China index has dropped 34.4%.

Below experts make the case for why investors should back the surging India market or turn their attention to out-of-favour Chinese stocks.

Performance of indices over 3yrs

Source: FE Analytics

The case for India

Sean Taylor, chief investment officer and portfolio manager at Matthews Asia, said while both Indian and Chinese equities can play a key role in portfolios, he prefers India.

“First, India's political stability and growth prospects are more favourable than China's. India's equity market recovered from a sharp decline when prime minister Modi's party secured a coalition government, which is expected to continue the progress on infrastructure, urbanisation and consumption,” he said.

The result may entice foreign investors to increase exposure to Indian equities as the election result shows that democracy is working, and checks and balances are in place. It is also expected that economic growth will accelerate under Modi’s third term, said Taylor.

“Second, China's macro indicators and catalysts are mixed and uncertain. China's equity market performed well in the last quarter, but its retail, consumer and property sectors are still weak. The government's policy changes and reforms may provide some support, but their scope and timing are unclear.”

Lastly, China's exposure to geopolitical risks is higher than India's with the former market potentially coming under pressure from the upcoming US presidential election.

“In contrast, India is less affected by the US election and more driven by domestic factors,” said Taylor. “India also has lower inflation than its peak and healthy corporate balance sheets which may allow for more monetary easing to help growth once the US starts its rate cycle.”

Conversely, China’s monetary policy remains tight relative to economic activity, he added.

Turning to the market directly, he noted earnings growth in India continues to outpace that of other emerging markets. “According to Bloomberg data, India's corporate earnings are projected to grow more than 15% annually for the next two years, with upward revisions reinforcing this optimistic outlook,” he said.

“In contrast, China's corporate earnings are expected to grow by around 10% during the same period, but these projections are accompanied by downward revisions.”

Although India is trading at a premium, with a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 23x its projected 2024 earnings compared to China's 9x, this “is likely to persist” if India's earnings growth continues to surprise to the upside.

“In contrast, China's investment outlook could improve if the government adopts a pro-growth agenda that boosts corporate earnings, especially given the current low earnings levels and lack of domestic investor confidence,” he said.

The case for China

Linda Lin, portfolio manager at Baillie Gifford, agreed with Taylor that investors need to strike a balance between the two countries, but was more positive on China.

She pointed to the recent rally of the Hong Kong market, where capital has flown from the emerging market managers rebalancing based on the high valuations of companies in India. She also said the quality of growth companies between the two countries was stark.

“If we look at the quality and potential for growth from both India and China, I think 41% of growth companies are still coming from China,” she said.

“Why does that matter? Because you are paying less than 10x earnings for the best growth companies in the emerging markets.”

She accepted there had been less intervention from the government to help stimulate the economy, but noted it is probably waiting until after the US election, when there will be a better understanding of the future trade landscape with America.

“Experts in China have been asking why China does not have an aggressive policy to boost the economy but the answer is it needs to see what the result will be in November [of the US election] and what the new policy will be against China,” said Lin.

Regardless, she noted there is outside money coming into the country, just not from the developed world. Although there has been a lack of Western capital coming into China over the past few years there are people buying from the Middle East, South America and other parts of Asia.

As a result, she does not believe the US election outcome will have as large an impact as it might have once had economically, with China “trading much more with ASEAN countries than the US now”.

Another positive is the Middle East, which is getting behind China’s green energy transition – an understandable alliance as the oil-rich region is likely to impacted mightily by China’s progress away from fossil fuels.

“They are very cognisant to work with China. This is not because of politics, it is because China’s long-term energy transition matters the most to that region. They have to come in. That is why we are seeing the supply of capital changing in the coming years,” she said.