The Jupiter India fund epitomises more than any other investors’ love affair with the world’s most expensive equity market.

The popular fund has amassed a £2.1bn war chest and was one of the most-bought regional funds in the first half of 2024.

It is also one of the most popular funds on Hargreaves Lansdown and Fidelity International’s platforms and for a good reason: it has doubled investors’ money over the course of three years.

It has a top FE fundinfo Crown Rating of five and has been in the first quartile of performance against the IA India/Indian Subcontinent sector over one, three and five years, falling to the second quartile over the past decade.

However there are signs that investors’ appetite for India is waning. In October, Jupiter India dropped out of Fidelity’s top 10 ranking for the first time in 2024.

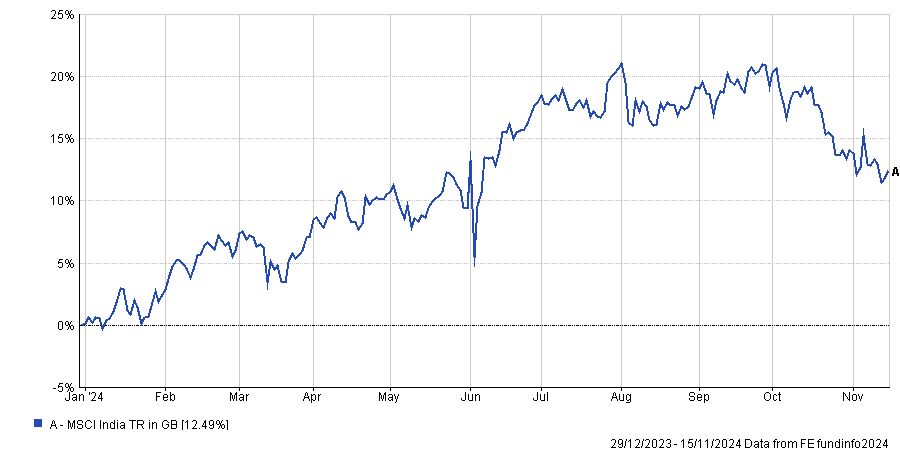

The Indian market as a whole has been selling off aggressively since the end of September, with Bestinvest managing director Jason Hollands saying that some of the steam may be starting to find its way out of the pressure cooker. “India is currently one of the few markets where valuations are even richer than the US,” he said.

Performance of index over the year to date

Source: FE Analytics

Below, we asked fund selectors who is right, the sellers or the buyers, and how to think about Indian allocations.

Bestinvest’s Hollands: In the short term, better opportunities sit elsewhere

For Hollands, the more cautious stance among institutional investors is due to concerns about hefty valuations, especially in the mid-cap part of the market.

“What differentiates Jupiter India from many of its peers is its greater exposure to small and mid-cap stocks, which might explain why professional investors concerned about frothy valuations in these parts of the market have been pulling money out, banking profits in the process,” he said.

At the headline level, Indian equities are trading at a 12-month forward price-to-earnings multiple of 24x and a price-to-book ratio of 4x, around 30% higher than the 10-year average. This is driven by domestic buying and a blizzard of recent initial public offers (IPOs).

But beyond that, the Indian long-term structural growth story remains intact.

“The fund is managed by a well-regarded and stable team who have delivered very strong returns. If you are a long-term investor and prepared to put up with short-term volatility, then this should be a hold,” Hollands said.

“However, in the short to medium term, the better opportunities probably sit with US equities outside of big tech, where the prospect of tax cuts and deregulation should give the current bull market extra legs.”

The Wealth Club’s Moyes: Don’t be a trader of funds

Jonathan Moyes, head of investment research at Wealth Club, said that Jupiter India is one of those funds that perfectly illustrates the pitfalls of trying to time markets and trade funds.

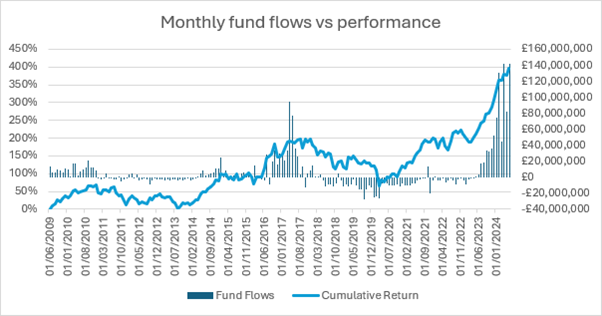

As a higher-beta exposure to India, the fund tends to be bought by investors chasing a period of strong performance, as the chart below illustrates.

Monthly flows against performance of Jupiter India

Sources: The Wealth Club, Morningstar

“Typically, after a period of strong performance, the fund attracts strong inflows and subsequently sees strong outflows when the Indian market is weaker. This is the last thing a manager wants to contend with,” Moyes said.

But his message was clear: Don’t be a trader. Investors should instead “be inspired” by the manager’s long tenure, with Avinash Vazirani in charge of the fund since 2008.

“This is a long-term investment that should not be tinkered with. For investors wishing to capture the growth of the India market, the fund has a strong longer-term track record of doing so. Investors that have attempted to time their entry and exit have fared less well,” Moyes concluded.

Quilter’s Moorhouse: It’s prudent to take profits

Carly Moorhouse, fund research analyst at Quilter Cheviot, opted for a prudent approach on the whole of the Indian market.

Indian valuations today reflect the opportunities for growth, as there are “several tailwinds from the macro story that make it an attractive market”.

“India has not run out of steam and it won’t for many years, given that the investment story that we are seeing there is driven by multi-decade structural changes,” she said.

“However, with the negative sentiment towards China driving emerging market investors into India, as well as a boom in recent years from domestic investors, certain parts of the market do look overvalued.”

Moorhouse concluded that given India’s strong performance, it could be prudent to take profits in areas that are looking stretched and to reallocate that into other markets that have lagged.