The US stock market has been outperforming other developed markets for decades now, inflating its value to a point where the US now accounts for 74% of global stock market capitalisation, as defined by the MSCI World index of 23 developed markets.

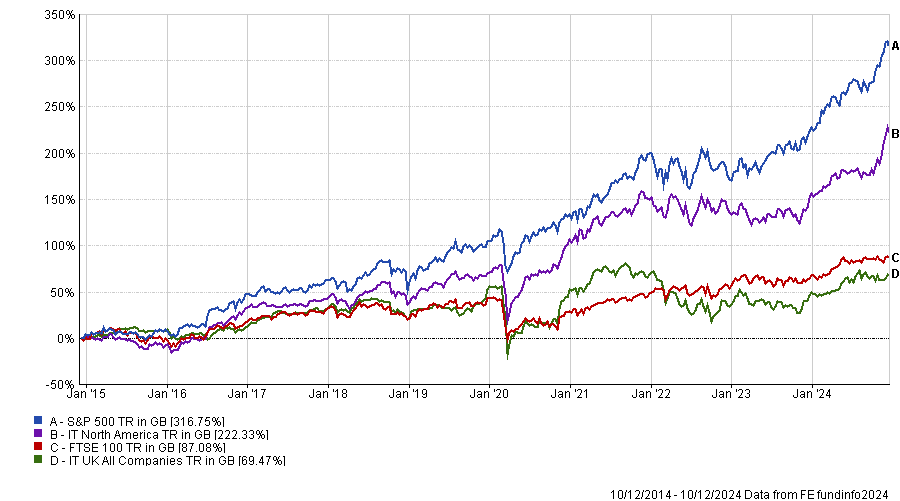

The S&P 500 has risen by 316.8% in the 10 years to 10 December 2024 in sterling terms, compared to the FTSE 100, which has risen by just 87.1%. Meanwhile, the average investment trust in the IT North America sector has risen by 222.3%, compared to 69.5% for the IT UK All Companies sector.

Performance of US and UK equity trusts vs benchmarks over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

But how much longer can this go on? The Association of Investment Companies (AIC) has just completed its annual fund manager poll, which canvasses opinion about which countries and regions will perform best the following year. Most managers (28%) expect the US to be the top performer once again next year, followed by the UK (24%) and emerging markets (16%).

I’m not going to take issue with any of the participants’ votes. But I have been struck by how many managers, commentators and investment advisers I have met recently who believe that the S&P 500 has reached such lofty valuations that it simply cannot continue beating other markets (I caveat this by saying I have heard this many times before!)

But I suspect I am not alone when I look at my global investment trust holdings, see such a heavy weighting to the US – especially to the very largest stocks – and worry that I am over-exposed to a relatively small number of the world’s most valuable companies, trading at record multiples of earnings.

Last year, the Magnificent Seven accounted for more than half of the S&P 500’s gain of 26.3%. So much for diversification!

Welcoming a broader rally

Investment trust managers have been expecting the US rally to broaden out beyond the Magnificent Seven and that has indeed started to happen.

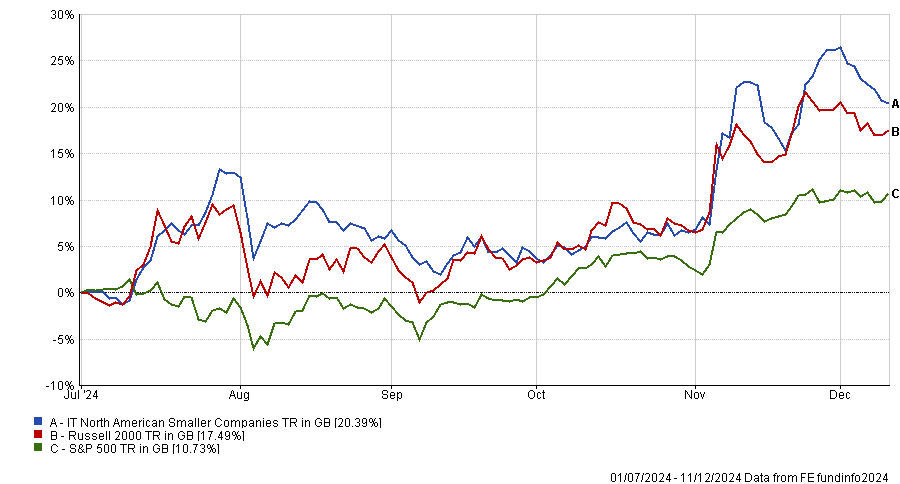

US smaller companies have outperformed large-caps since July and investment trusts in the IT North American Smaller Companies sector have done even better, as the chart below shows. The Russell 2000 index hit an all-time high just last month as investors continued their rotation into small-caps and value stocks

Performance of sector vs small- and large-caps since July

Source: FE Analytics

We’ve also seen the contribution to the S&P 500 from the Magnificent Seven stocks fall away since the sell-off in the summer.

Intuitively, a broader stock market rally seems like good news – and it quite obviously reduces the risk of a market crash, so it is also a less stressful market in which to be invested. And for active fund managers, it also tends to be a boon. Indeed, research produced by Morgan Stanley into the history of stock market concentration since 1950, released this summer, unearthed some fascinating trends.

Focus on concentration

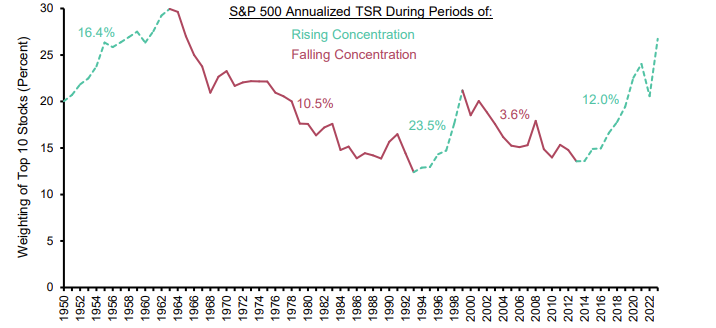

Morgan Stanley reported that high market concentration is nothing new. The value of the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 has frequently exceeded 20% and hit the previous record of around 30% in the 1960s.

This was when household wealth had soared, seemingly every household was buying a car, and the stock market was dominated by motor manufacturers such as Ford and General Motors, and the oil giants, including Texaco, Mobil, Gulf Oil and Chevron.

That record has been exceeded as this year, as the weighting of the top 10 stocks reached more than 35% in the summer, but it has been plateauing since, and we’ve seen a greater proportion of stock market returns come from other parts of the market. As a result, many experts think we are at a turning point.

What it means for investors

Crucially, history shows that when market concentration is increasing, stock market returns also rise. And when concentration dissipates, as it invariably does, market returns fall. That’s not to say they turn negative, but they grow less quickly – at an index level at least.

In the period of rapid concentration in the 1950s and 1960s, annual returns on the S&P 500 averaged 16.5%, but when the market broadened, returns fell to an average of 10.5%.

More markedly, in the 1990s, when the S&P 500 was increasing in concentration, returns averaged 23.5%, but in the noughties, when it was dissipating, returns fell to 3.6%. There were obviously other factors at play, such as the tech crash, which led to an immediate and very rapid dilution in concentration. Nevertheless, the trend is remarkably consistent.

S&P 500 annual returns during periods of rising and falling market concentration, 1950-2023

Sources: Morgan Stanley, FactSet and Counterpoint Global

Just in the past decade, however, annual returns have averaged almost 13%, so where from here?

What history says will happen next

If we are indeed seeing a sustained broadening of the US market, history suggests two things: returns will slow at an index level, and a larger proportion of actively managed funds will outperform, as increased market breadth favours more diversified portfolios.

According to the same research by Morgan Stanley, less than a third (30%) of actively managed US mutual funds outperformed the index when concentration was rising, but that increased to nearly half of actively managed funds (47%) when concentration was falling. Admittedly, the research is referencing mutual funds rather than investment trusts here, but the principle of a broader rally favouring skilled active management should hold.

Will the US continue its world beating run next year? Heaven knows! But history suggests that we are entering a more fertile period for active fund managers, with a greater universe of attractive opportunities to choose from. And investment trusts, with their unique capacity to take on gearing, and explore asset classes beyond conventional equities, are in a prime position to capitalise.

None of this is to say that actively managed funds are going to outperform the index year in, year out. But given the current market broadening, the odds may just have improved.

Annabel Brodie-Smith is communications director of the Association of Investment Companies. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.