One of the biggest issues for investors with sustainable investing lies with the lack of clear definition over what it actually means: sustainable investing can mean different things to different people.

As Good Money Week begins, Trustnet asked several market experts how to resolve the confusion caused by the lack of definition for sustainable investing.

Good Money Week is an annual event which aims to raise the awareness of sustainable, responsible and ethical finance.

However, sustainable investing covers a broad range of different funds.

The most well-known today is ESG – or investing in companies meeting specific environmental, social & governance criteria – and is often used synonymously with sustainable investing.

There are also ethical, impact and SRI (socially responsible investing) funds which fall into the sustainable category.

Nevertheless, they all share the common thread of investing for better social and environmental outcomes.

Sustainable investing has moved a long way from being a niche area of the market to becoming a competitive strategy, coming through particularly strong in 2020 as companies falling under the ESG label have performed better than their peers.

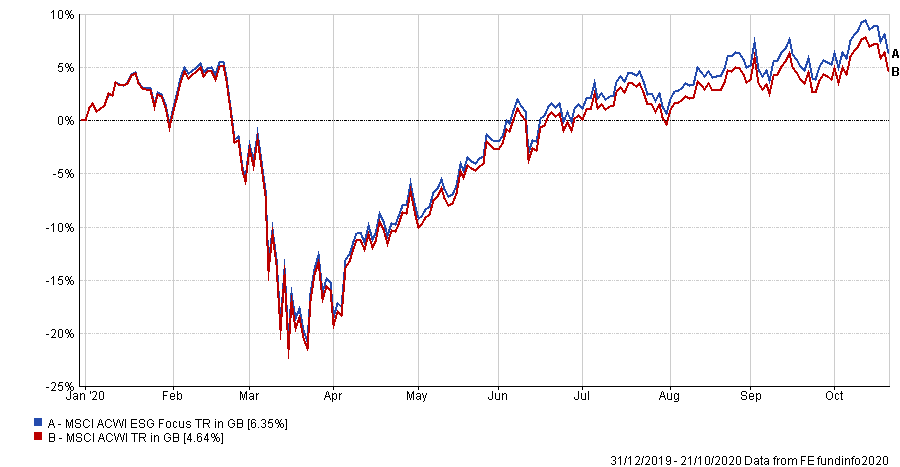

The MSCI ACWI ESG Focus index – comprising global stocks with a strong ESG remit – outperformed the broader MSCI ACWI benchmark, making a total return of 6.35 per cent year-to-date compared with a 4.64 per cent gain for the latter.

Performance of MSCI ACWI ESG Focus index vs MSCI ACWI YTD

Source: FE Analytics

And this has been reflected in sales data.

The latest edition of the Calastone Fund Flows Index (FFI) found equity funds with an ESG mandate saw £588m inflows during September. By contrast equity funds without an ESG focus saw outflows of £203m.

However, while the strategies are gaining in popularity, there has been a lack of definition on exactly what constitutes a sustainable fund entails which has left some in the industry on the side lines waiting for a concrete definition.

So what is the solution?

Rebecca Craddock-Taylor, director of sustainable investment at Gresham House, agreed that the language aspect of sustainable investing has been a major challenge.

She said the sustainable investment space needs clear classification on the different denominations of sustainable funds rather than just one standardised ESG rating.

Craddock-Taylor said: “I think what’s important is a standard for labelling what is a sustainable fund, a socially responsible fund and what is an ethical fund. And I think that’s where the standardisation is more required.”

Although some have suggested developing one standard ESG rating, Craddock-Taylor said this would be the wrong path.

“If there’s one standard on how to produce an ESG rating then companies learn how to get a good ESG rating and get included in these strategies,” she explained.

Another solution could be new government legislation, something which is currently playing out at policy level in the EU. The bloc has been pushing through legislation to support the transition from a fossil fuel economy into a renewable one in recent years.

And this was recently seen when members established the Coronavirus Recovery fund – a €750bn stimulus package designed to help bloc nations cope with the economic impacts of Covid-19.

The package was approved with the stipulation that funds be channelled through the pre-existing European Green Deal meaning the EU’s recovery from Covid-19 has been built around a goal to tackle climate change.

New terminology looks set to push this support for sustainability into investment markets.

The EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) will come into effect next March

Simone Gallo, managing director at MainStreet Partners, said: “This regulation is a huge step in the right direction to help reduce ambiguity around sustainable investment. There will be more to do, but explicit and detailed definitions on a Europe-wide scale will be a landmark development.”

Gallo said the permeation of so much jargon over what SRI, ESG, ‘impact’ and ‘sustainable’ means has left many investors confused, adding that upcoming regulation should help provide some clarity.

The goal of the new legislation is to clearly separate the investment vehicles that actually integrate sustainability into the strategies from ones which don’t.

This process, Gallo, said is two-fold.

One, all investment strategies “will be required to disclose the ESG risks linked to them, or state openly and publicly through their websites the absolute lack of intention to take into account such elements”.

Secondly, it will be easier to distinguish between different types of strategies.

“There will be a clear distinction between generalist strategies that integrate ESG factors into the investment process and more thematic strategies that intentionally pursue quantitative social and environmental objectives,” he said. “Ultimately, this means use of the term ‘sustainable’ will only be allowed on a specific group of products.”

While this legislation will only apply to European funds, Foster Denovo’s Declan McAndrew said the practice of fund managers being honest about sustainability in their processes is important for tackling the issue.

McAndrew, who is head of investment research at Foster Denovo, agreed that, in a person’s day-to-day life their engagement with sustainability is very personal and often ends up reflected in their investments. For some it might be a priority and for others it may not be important at all.

“To actually say ‘we don’t care about sustainability’ is actually a bit unsayable in 2020 particularly. Although those who go ‘this is our process we don’t adhere to that [ESG] at all’ that’s very clear. It’s where there’s more ambiguity going ‘we kind of do it’.”

It’s in these cases of lacklustre commitment to sustainability that confusion arises he said.

He explained: “I would prefer it if they were fully into sustainable or were just financial only. Because then that is a clear choice between them.

“Those that go ‘we need to have some sort of overlay’ invariably they don’t actually believe in it and ultimately the process doesn’t come with the outputs that are justifiable.”

What needs to happen, according to McAndrew, is for managers clearly lay out what their definition of sustainability is and demonstrate it in their process and reporting. And then to let investors decide whether it’s the right option for them.

He said: “I do think that if fund managers, in particular, set out their stall and prove that by their impact reporting, then I think that’s fair enough for advisers to take that and go ‘does that align with our definition?’.

“Define your own definitions and then see whether you agree with what the offerings are.”