Semiconductor manufacturer Nvidia has been the most successful company of the past few years. Portfolio managers who own it have seen their returns skyrocket and those who don’t say it’s a controversial stock to buy.

Julian Bishop, co-manager of the Brunner investment trust, belongs to the latter cohort, but if he could go back, he would certainly buy it, he admitted, as not owning Nvidia has had the greatest negative impact on the trust over the past year.

“When calculating the combination of percent declines and position size, the worst active contributor for us was not holding Nvidia. That cost our relative performance quite a lot,” he said.

A natural question could therefore be why he still hasn’t bought it, and Bishop said this conversation has been “talked about to death” at Brunner.

The pros are fairly evident and self-explanatory. According to Bishop, Nvidia is “incredibly profitable” and far from being a “dot-com bubble-type, nonsense stock”. It also has “a very high market share”, and what it does is “absolutely critical” to the build-out of artificial intelligence (AI) infrastructure.

“These are all things that we would typically look for in a company,” admitted the manager. “On top of that, there is also the exceptional growth in the past few years, as AI has exploded onto the scene.”

But there are quite a few cons that stopped the Brunner portfolio from welcoming the semiconductor darling.

Firstly, people are spending “an absolute fortune” on AI already. Next year, Nvidia is expected to sell $100bn worth of chips, which is “by any stretch of the imagination, a vast amount of money”.

Around that, one must also take into account the data centres needed to make AI work which “would probably add another $100bn” to the amount tech companies are spending.

“With $200bn of costs in a year, they would need to generate at least $400bn of sales to get an adequate return,” he said.

“But at the moment, we're not even close. Let's not forget that at the moment, no one is actually making any money with AI.”

Beyond this question mark over demand, there are also barriers to entry to consider, as “everybody is trying to break the moat around Nvidia”.

Because it only sells to a few customers (the likes of Meta, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Tesla), it is even more vulnerable, as they are all trying to develop their own versions.

“When Microsoft is spending $10bn a year on these chips, its procurement department has every interest of breaking down Nvidia’s moat,” Bishop said.

“There is a saying in technology that at the end of the day, all hardware is a toaster. Ultimately, everything, no matter how complex it looks, can be replicated by somebody somewhere, and it becomes commoditised. With time, prices deflate and profit pools get eroded.”

The second question mark was therefore: How much in the ecosystem is built around Nvidia? Or, to use an analogy: Is Nvidia Apple, or is it Samsung?

Apple makes great profits selling smartphones for the only reason that it has been able to create an ecosystem around them – the apps, all the software, the brand, the retail network. But most smartphones are commoditized, the manager explained.

“You would be amazed at how little money Samsung makes making smartphones,” he said. “Even though it is probably making as many smartphones as Apple, they're the commoditised end of the spectrum.”

Nvidia does have some software and systems around what it does, it isn't just a microchip that might get commoditised with time. So for Bishop, the real debate is how much of an ecosystem is around Nvidia, and whether that will protect it against competition.

Finally, the manager was also mindful of previous technological revolutions. All the top companies at the time of the dot-com bubble, for example, “just faded to nothing”.

Bishop recalled Cisco Systems, which built all the routers that were used to sort internet traffic, or Global Crossing, which laid the fibre optic cables across oceans that exist to this day but went bankrupt because “loads of other people had cables too”.

“Companies such as these did the world a favour by building incredible infrastructure that allowed all this technology, but it is companies down the road, such as Amazon and Google, that made use of this technology and the most of the money. We think it might be similar this time,” Bishop said.

“I have no doubt that AI’s influence will be probably overestimated in the short term and underestimated in the long term. But it's not quite clear to us that the people who build it will be the ones that make money.”

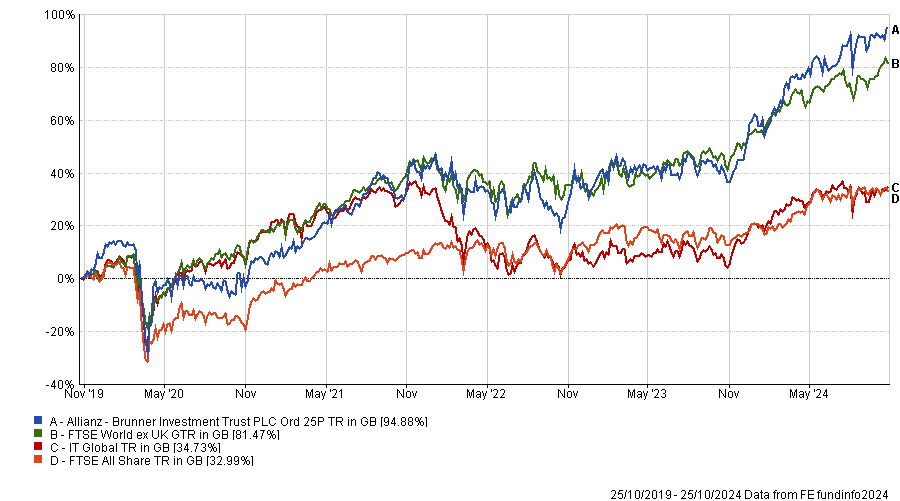

Performance of trust against sector and index over 5yrs

Source: FE Analytics

So far, these considerations have stopped Bishop from buying Nvidia, preferring instead “guaranteed winners” such as Taiwan Semiconductors, the trust’s best contributor over the past year (which makes up 3.3% of the portfolio), and Microsoft, the trust’s top holding at 6.4%.

But he “certainly wouldn't rule out” buying it in the next 12 months or so.

“It's part of our job to protect our clients from the madness of crowds when bubbles develop and irrationality can settle in. But Nvidia is not in that class, and the valuation, if it can prove that the moat is strong enough, is not crazy. It is possible we could buy it in the year to come, absolutely,” he concluded.