Investors who focus solely on ESG stocks risk falling into the same trap as those who fell foul of the dotcom bubble in the early 2000s, according to Newton Investment Management’s Andrew Parry.

ESG, or Environmental, Social and Governance strategies soared in 2020, with Rathbones’ Will Mcintosh-Whyte pointing out sustainable investments shied away from heavy-polluting industries, so were largely unscathed by the slowdown in international travel and lower demand for fossil fuels.

Furthermore, he noted sustainable funds have a high exposure to many technology companies that made life easier in a socially distanced world, as well as clean energy.

“Power grid operators took advantage of the cheapest energy sources to meet demand, and in many cases this turned out to be renewables like solar and wind power whose costs have plummeted over the last decade thanks to continuous technological innovation,” he said.

“There is also a global push towards cleaner energy, providing a regulatory tailwind to the sector.”

However, Parry warned broad industries and solution-based ideas do not necessarily constitute good business models, and investors must avoid lumping companies under one banner as they are exposed to different drivers and risks. He said this has been exacerbated by excess liquidity, which has led to excessive valuations.

“When profits cease to matter, you know problems are brewing,” he said. “Investors need to embrace the successful implementers of sustainability solutions into business practices that drive efficiency, build brand value, and help companies remain relevant in a changing world.”

Parry added that being ‘green’ is not enough for a company to be successful, and as the dotcom bubble, and ‘Nifty Fifty’ stocks of the 1970s and 1980s showed, fashionable companies often fall by the wayside.

“As money floods into sustainable investing, not all of the most exciting solution providers will survive the harsh reality of market forces, even though we can expect the innovations and benefits to endure,” he said.

“Money traditionally flows to the best ‘story’, rather than to the problems that are hardest to solve.”

Neither managers suggested that there was a bubble in ESG stocks, but said parallels could be drawn in terms of both investor sentiment and rising valuations.

And Mcintosh-Whyte reiterated Parry’s point about the dangers of lumping companies in together just because they operate in the same sector.

“Look at it this way,” he said. “If demand for streaming video suddenly tapers off as we venture back into the wide world, it’s likely Amazon will be sheltered because its business is so diversified these days, but Netflix will be exposed.

“We can’t lump companies together into one convenient ‘sustainable’ bucket just because they seem to tick all the right boxes. They do different things, serve different markets and are affected by different forces.”

Parry said that such a blanket approach was exactly what happened in the dotcom bubble.

“For a while, it was impossible to do any wrong if you were a technology investor,” he continued. “The environment was the investment equivalent of shooting fish in a barrel.”

However, the mood shifted in 2003 as monetary conditions tightened and the savvy, early investors quietly left before the bust.

“It wasn’t that the long-term prognosis on how tech would change our lives was wrong; if anything, we were too modest about the shape of things to come,” said Parry.

“The problem was that too much money was chasing too few profitable and enduring business models.”

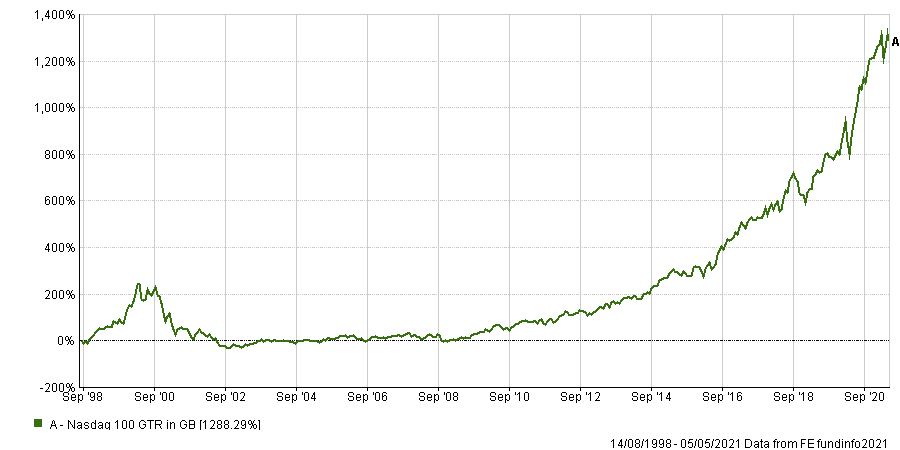

Performance of Nasdaq 100 since 1998

Source: FE Analytics

Amazon, for example, a survivor of the bust, took almost a decade to regain its 1999 market high, while the Nasdaq 100 index took until 2014.

Parry finished: “The first rule of being a sustainable business is to survive – business models and valuations matter, and sustainability matters.

“The trouble – for businesses, investors and Mother Earth – is that you won’t get the latter if you ignore the former.”