The Chinese government’s crackdown on private education and technology this year caused both of these sectors to plummet, dragging down the rest of the market, and deterred many fund managers from investing in the world’s second-largest economy.

In a recent article on Trustnet, David Lewis, a co-manager on the Jupiter Merlin range, said that his team had been questioning its exposure to the Chinese equity market for some time and described the intervention by the government this year as “the final straw”.

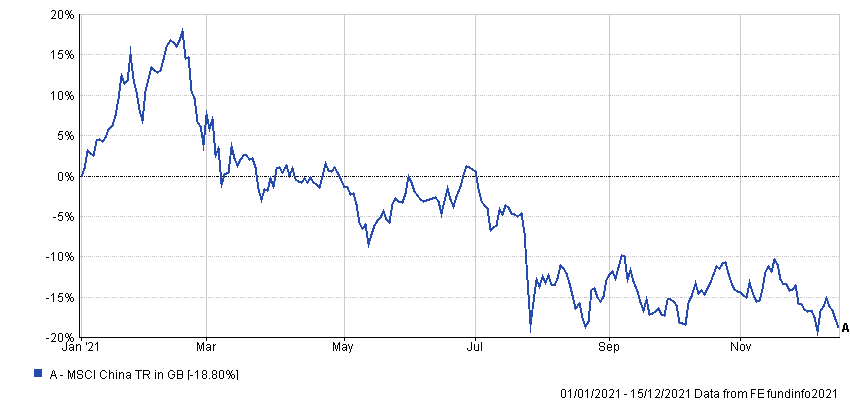

Performance of index in 2021

Source: FE Analytics

“We feel like the mood music is very much away from those minority shareholders, which we are always going to be,” he said. "We do not feel that our interests are going to be looked after by investing in there.”

Another high-profile casualty in China’s stock market this year is Evergrande, the country’s second-largest property developer, which has just defaulted on its debt. Yet while governments often step in to prop up large companies that are going through difficulties, Matthews Asia investment strategist Andy Rothman (pictured) claimed that the opposite was true here and that the Chinese government caused Evergrande’s problems on purpose.

“Government officials have been expressing concern about Evergrande for many years,” he said.

“About a year and a half ago, the government came out with a policy called Three Red Lines. This was designed, I think, to stress test the worst-quality, riskiest developers in China, and Evergrande was at the top of its list.”

Three Red Lines insisted upon the following three ratios: liabilities to assets (excluding advance receipts) of less than 70%, net gearing of less than 100%, and cash-to-short-term debt of more than 1x. Developers who breached the rules faced caps on their ability to borrow.

While this policy made it harder for companies like Evergrande to obtain further financing from banks, Rothman said this alone wasn’t enough to push it over the edge.

“So in May this year, the government went to the banks and told them to significantly restrict mortgage lending to new homebuyers,” he continued. “As a result, the housing market froze up a couple of months later.

“Evergrande’s problems were, in my view, deliberately triggered by government policy in an effort to reduce risks in the financial system associated with the property market and promote consolidation in a very fragmented industry.”

However, Rothman said that Evergrande’s failure was not a systematic risk in the same way the sub-prime mortgage in the US triggered the financial crisis.

Although Evergrande was China’s second-largest property developer by sales last year, it still only accounted for about 5% of the market.

Meanwhile, the Chinese property market is less reliant on debt than most developed nations – homebuyers need a deposit of about 20%; for buy-to-let investors, this figure rises to about 50%.

This was compared with a median figure of 2% in the US in the run-up to the financial crisis.

“Also, Chinese banks hold their mortgages to maturity,” Rothman continued. “There are a lot of incentives to do good due diligence, as opposed to the US where banks almost always sell off immediately, so they don't really care.

“All the mortgages are kind of plain vanilla, there is nothing like the options market we see in the US and other places.”

Of more concern to investors may be the continued interference in listed businesses. There were even worries that the meddling by the ruling Communist Party this year was because it is ideologically opposed to private wealth accumulation, making further interventions likely.

Rothman admitted another reason for the crackdown on the property sector may have been related to Chinese premier Xi Jinping’s common prosperity policy, which is aimed at making society more equal, and concerns that large parts of the population were priced out of the housing market in urban areas.

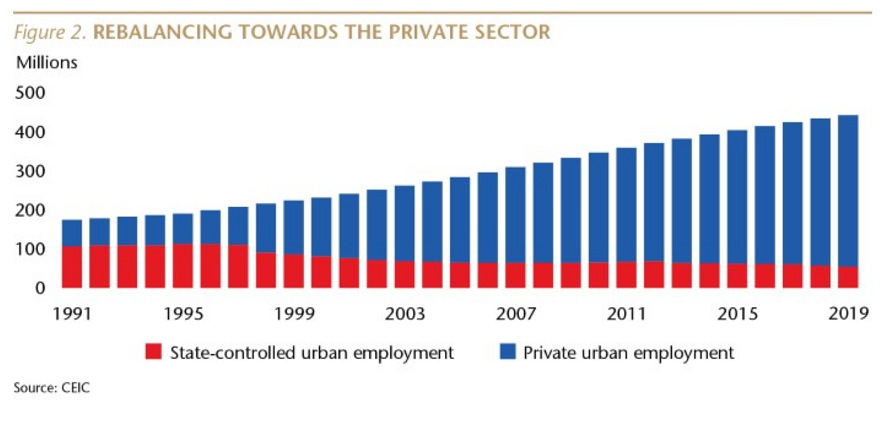

However, he disputed claims that government intervention this year formed part of an ongoing strategy to roll back the private sector reforms of the past few decades.

“Some people even say that Xi Jinping wants to go back to a Maoist period of China,” Rothman continued.

“I don't see any evidence to support that, it is certainly not what he is saying: he continues to talk about creating more opportunities for more people to get rich.

“It's probable that if he were candid he would say, ‘I'm not sure we need that many more billionaires. But I think we need a lot more millionaires’. And from an investor's perspective, that's fine.”

He added that private sector economic reforms have driven most of the job creation and innovation in China over the past few decades, which was the main reason the Communist party has been able to cling on to power.

The strategist admitted Xi Jinping was wary of rising inequality in terms of wealth and access to education and healthcare. Anti-competitive practices by big companies restraining growth in smaller challengers also appeared to provoke his ire. Yet Rothman pointed out debates around these issues were also prominent in many developed countries.

“But China has acted much more rapidly and aggressively,” he said. “And typically, like with property and Covid, it has overdone it. But now it’s backing off. If we look at the past few weeks, we've seen several indications that the policy tightening in China has bottomed out and we're now seeing the beginnings of a modest easing cycle in several ways.”

Other investment professionals were less confident. Oscar Yang, co-manager of the Impax Asian Environmental Markets fund, said: “These crackdowns exemplify the policy risks facing investors in China. Our sense is that these risks have not abated, especially ahead of the 20th Communist Party Congress in 2022, which will decide the leadership and the high-level policy direction for the next decade.”