Inflation has remained persistently high across developed markets as last week’s December data proved, surprising markets and disappointing investors who were hoping that central banks would cut interest rates imminently.

Even before the latest inflation prints, experts were already worried that inflation could stay higher for longer.

Paul Skinner, investment director at Wellington Management, told Trustnet last week that inflation would prove “far stickier and more persistent” by the end of the this quarter than the market and central banks are expecting.

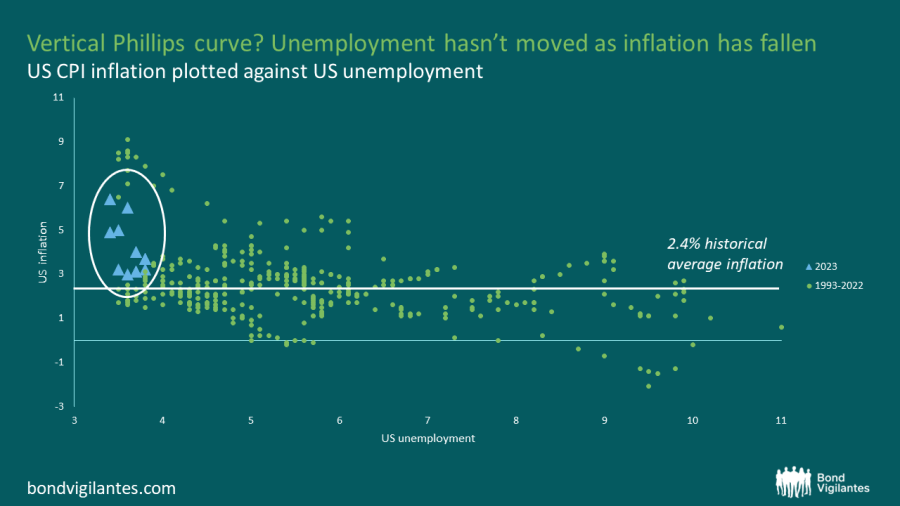

Although central banks have tamed inflation for essentials such as energy and food, Skinner stressed that wages remain elevated and the labour market has been resilient.

He said: “Our fundamental belief is that the demand for labour is going to support inflation and create volatility in the inflation rate.

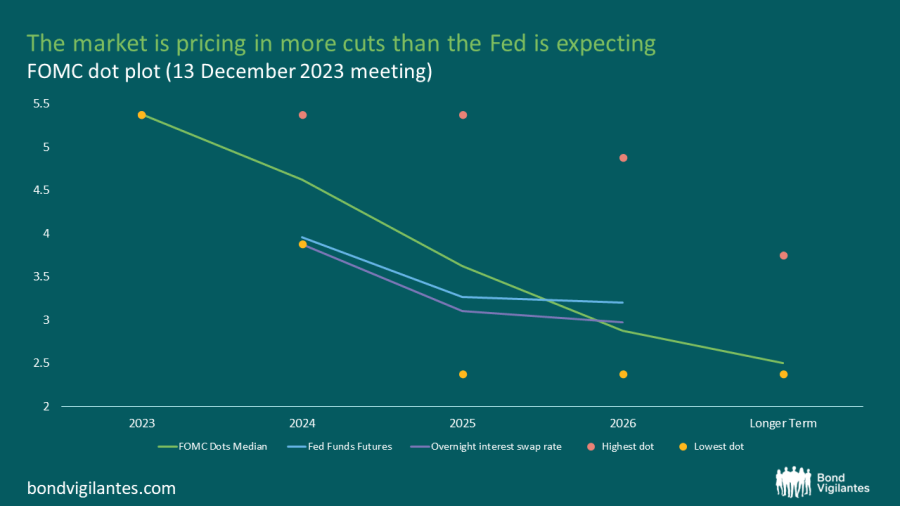

“The market is expecting rate cuts to start in March. That's just the time when we see inflation being a little bit stronger than the market is expecting.

“I don't think it's going to create a scenario where banks start raising rates again, but it could well put them on hold and that would disappoint the market's current thinking. You’ve got to be careful that you don't get sucked into this overly optimistic view of where inflation is going to be.”

Source: Source: Bloomberg, M&G

On a long-term view, Skinner believes that inflation will remain higher and more volatile than over the past 15 years due to structural drivers.

One factor is linked to demographic trends in developed markets, where means there are fewer workers available to fill job vacancies.

Skinner said: “We have significant demand for labour and that is going to keep wage costs elevated. There is an argument that artificial intelligence is going to release a great productivity cycle, but in our view, it is going to take a while for it to work through.”

Another factor that supports higher structural inflation is deglobalisation, as governments are looking to onshore production.

Skinner added: “That's intrinsically an inflationary process. Because we had loads of workers that did things very cheaply, we were importing deflation and all benefited from globalisation. Now we've got the opposite: we're onshoring. It's costing money, there are fewer benefits of scale.”

These views were echoed by Jonathan Gregory, head of fixed income UK at UBS, who cited the green transition, larger defence spending and government budget deficits as further forces supporting higher inflation.

These factors could lead central banks to widen their inflation rate target bands or change their inflation targets.

“We could be in the last innings of monetary policy and inflation targeting as we know it,” he said. “Monetary policy regimes were quite distinct 100 years ago, but they have changed over time because monetary policy is in the service of political goals. When those goals haven’t been met, policy has changed.”

Source: Source: Bloomberg, M&G

While inflation may remain structurally higher and more volatile, Skinner does not believe that it will be a “frightening” inflationary period. Instead, he suggested that the macroeconomic environment will be more similar to the one prior to the 2010s.

“We've gone from a period of 10-15 years of low growth and low inflation into a period that's much more like the previous 50 years, where we had much more cyclicality in economic and inflation rates,” he said.

“You'd have high inflation, sometimes high growth and stagflation at other times. Rotating between those is much more normal than the 15 years we’ve just had.”

Skinner also warned that the market has gone off the concept of a recession and is assuming a perfect scenario in which the Federal Reserve will get inflation down without creating a recession.

He said: “A lot of the forecasts predict growth to fall to zero, then plateau and then come back up. That's really optimistic. It's very difficult with such a clumsy tool as monetary policy to engineer our economy to neatly touch zero and then come back up.”

While he does not expect a deep global recession, his prognosis is for a shallow recession.

Although a recession should be a good economic backdrop for bonds, Gregory believes it will just be an “okay” year for the asset class rather than a fantastic one given that the market has already priced in most of the “good news”.