Investors need to be preparing their portfolios for a major change in the market backdrop, according to Bank of America’s Michael Hartnett, as it looks like the end is looming for four decades of lower inflation.

The year so far has seen bonds and parts of the stock market hit hard by fears that a vaccine-led economic rebound from the coronavirus crisis will spark higher inflation. Few doubt that inflation will move higher from the low levels we have gotten used to, although it is uncertain how orderly or disorderly this shift will be.

Hartnett, chief investment strategist at Bank of America, said investors need to start thinking about how they will prepare their portfolios for higher inflation as he believes 2020 marked “the secular low point for inflation and interest rates”.

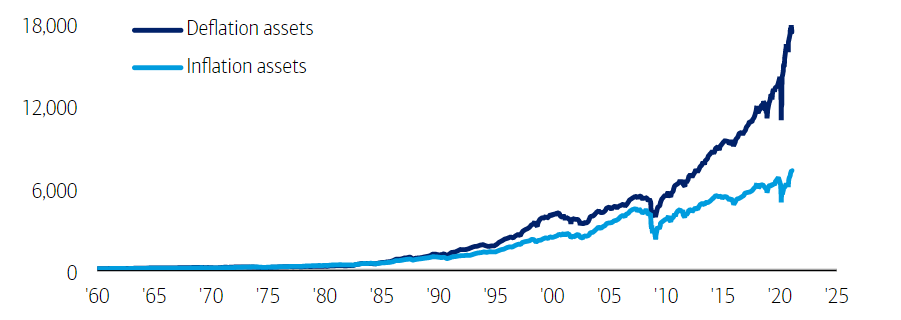

Inflation assets vs deflation assets

Source: Bank of America

He argued that there are six factors behind the secular decline in inflation over the past 40 years: central banks’ inflation targeting; ‘smaller’ governments (privatisation, deregulation, lower unionisation); globalisation increasing the supply and reducing the cost of goods, services and labour; technological disruption; demographic effects like immigration and late retirement increasing the supply of workers; and soaring debt levels causing low money velocity.

“Lower inflation has caused lower interest rates, a great bull market in bonds and an epic rise stock market valuations since 1981. Since the global financial crisis, the radical introduction of central bank quantitative easing programmes has fuelled a rapid inflation of financial asset values, exacerbating wealth inequality (the value of US financial assets is now six times the size of the economy),” he added.

“We believe 2020 likely marked a secular low point for inflation and interest rates due to a reversal of deflationary secular factors, fiscal excess and an explosive cyclical reopening of the global economy creating excess demand for goods, services and labour.”

Many of the six factors that have pushed down inflation over the past four decades now look as though they will drive inflation higher.

Central banks, for example, are now targeting higher – rather than lower – inflation and are likely to do so for some time, while the electoral shift toward populism over recent years lends itself to ‘bigger’ governments that are more likely to pump money into the economy.

In a similar vein, electoral populism and the pandemic has reversed some elements of globalisation, which will raise the price of imported goods and services. Technological disruption of labour remains potent deflation force but taxation and unionisation appear to be moving against tech.

Finally, Hartnett said that ageing populations are curtailing the growth in labour supply and will hand more wage bargaining power to workers while debt has shifted from household/financial sectors to government sector, which has a vested interest in inflation to lower real cost of debt.

If the world does move from an environment of low inflation to one where it is higher for a sustained period, then investors have to prepare their portfolios. Hartnett said economic and investment turning points such as this usually have “profound implications” for asset allocation and market leadership.

“We believe the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020/21 coincide with a secular turning point in inflation; at a minimum it has accelerated policymaker’s ‘War against Deflation’ that has been brewing in recent years,” he explained.

“Historical analogues are imperfect but comparisons with the late-60s, early-70s are good. In the '50s and '60s inflation and rates were low and stable, and equity multiples expanded greatly. But by 1966 inflation and interest rates suddenly became unanchored on the back of large budget deficits, an easy and complicit Federal Reserve, ‘Great Society’ policies to address inequality, civil unrest and Vietnam.

“That 1965-68 ‘Twilight Zone’ when expectations and unease on rates and inflation started to grow is where we are today. Bond yields rose but it was not fatal; equity markets entered a trading range. The period obviously ended badly in the early '70s when both inflation and rates surged on the back of the Nixon dollar devaluation and first oil shock.”

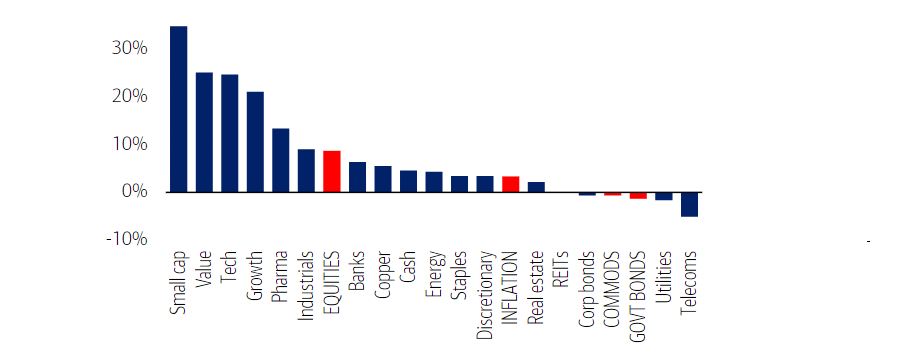

Cross-asset & equity sector annualised total returns, 1965-1968

Source: Bank of America

The chief investment strategist said the main investment lessons of the late 1960s were:

• A period of high, volatile bond yields did not cause a bear market in stocks but it did end the powerful post-WW2 uptrend in stocks. The Dow Jones hit 1,000 in 1966 and traded in a range with that as its ceiling for another 15 years.

• A barbell of solid buy-and-hold growth stocks (the Nifty 50) and small-cap value led to “powerful outperformance”.

• Conditions were very positive for commodities and small-caps but “highly destructive” in real terms for bonds and large-caps.

He added: “We believe the long-term asset allocation implications of 2020s inflation are bullish real assets, commodities, volatility, small-cap, value and Europe, Australasia, Far East/emerging market stocks, and bearish bonds, US dollar and large-cap growth.

“While it’s too early to price a disorderly jump in inflation and yields, note it’s thus far in 2021 the fourth worst start for the 30-year Treasury in past 100 years, best start for oil since 1974 and equity investors have experienced an epic reversal in Nasdaq versus Russell YTD.”

All this leads Hartnett to conclude that investors should consider seven broad guidelines when positioning their portfolios for inflation in the 2020s, whether orderly or disorderly.

Firstly, they should assume lower returns across asset classes. The annual gains of 10 per cent or more from stocks and bonds of recent decades are likely to fall to 3-5 per cent.

Secondly, prepare for higher volatility in stocks, bonds and currencies.

Investors should also be embracing greater asset allocation diversification. Bank of America said the optimal asset allocation split looks to be 25/25/25/25 between stocks, bonds, commodities and cash.

The fourth point to consider is that negative returns are likely to be the “new normal” in fixed income. The bank’s bond strategists prefer high-yield and leveraged loans; they would avoid long-duration government and corporate bonds.

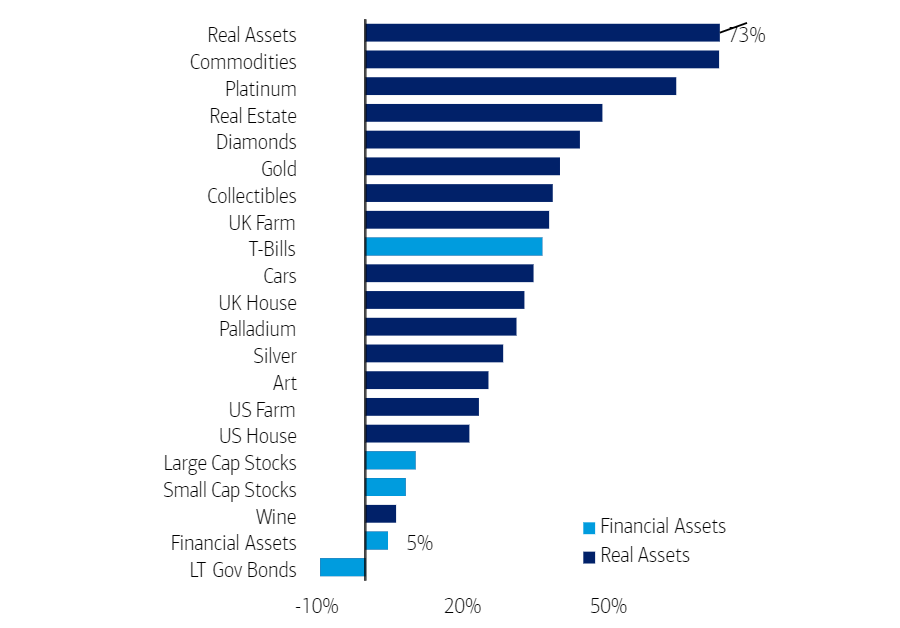

Next, real assets like property and commodities could outperform financials assets, as they tend to be more correlated with inflation. This is illustrated in the chart below.

Correlation of real & financial assets with inflation since 1950

Source: Bank of America

Harnett also argued that US dollar debasement plays such as commodities, resources and emerging markets “should ultimately work”. BofA’s commodity strategists are most bullish on copper and oil, citing peak demand in 2030.

The seventh portfolio construction point to consider is overweight assets such as small-cap stocks that are price-takers, not price-makers, as they ultimately benefit from inflation.