In a recent article published on Trustnet, Kleinwort Hambros chief investment officer Fahad Kamal claimed that inflation had become embedded in the US economy. However, his colleague Thomas Ghelen pointed out there were signs that the Federal Reserve’s tightening cycle was already having an impact.

Yannis Gidopoulos, an analyst at Montanaro, went even further, claiming that the spike in US inflation was always likely to be temporary and will soon move significantly lower. Below he explains the three main reasons why.

1. CPI is a lagging indicator

Gidopoulos pointed out that CPI is skewed towards stale data, making it unhelpful for figuring out what inflation will look like in 12 months – which is what the stock market tries to discount.

In addition, he said it is only relevant to interest rates insofar as it is supposed to indicate whether the economy is overheating.

He claimed the September CPI print of 8.2% in the US is of no use for this purpose, partly due to the fact housing costs (‘shelter’) account for 32% of this figure.

Shelter is made up of rent prices, and “owners’ equivalent rent”, a fictional number approximating what homeowners would be paying if they were tenants. Gidopoulos said this measure is unhelpful for two reasons.

“First, it’s a deeply lagging indicator, because rents are fixed for the term of a lease before being repriced, with a lease typically being around 12 to 24 months,” he explained.

“So you get an inflation number published reflecting price increases from the year before that.”

He said another issue is that rising mortgage rates put people off buying houses, which is deflationary. Yet it raises demand in the rental market, disproportionately pushing up CPI.

“The housing market has already turned (rent usually lags housing),” Gidopoulos continued. “House prices in the US went down in September, for the first time in about a decade. But these prices do not get captured in the CPI print, which instead treats home-buying transactions as ‘services’ and imputes a lagging rental price on them.”

Next, Gidopoulos moved on to inflation expectations. These are almost as important as inflation itself and there are concerns we could end up in a self-fulfilling cycle similar to the one seen in the 1970s.

Yet there is no sign of this happening. According to the analyst, this could be because inflation is regarded as transitory in the real economy, insofar as the average shopper has already noticed a plateauing of prices.

“My local pub has raised its prices from about £5 a pint to nearly £7. Will they be £7 in six months? I don’t know, but I feel pretty confident they won’t be £9,” he said.

“High inflation needs to be sustained for a long time before becoming embedded in consumer psychology. But the economy has gone from inflation trough-to-peak in something like 12 months. Nowhere near enough to move long-term inflation expectations.

“Therefore, the feedback loop which in the textbooks posits that I as a consumer will rush to the pub to guzzle as many pints as possible – in fear of prices continuing to rise at the same rate, thereby causing prices to rise further – simply does not hold.”

He added: “I can assure you I’m drinking fewer pints at these prices, not more.”

The real fear when it comes to inflation expectations is that workers will demand that wages keep pace with rising prices, creating a vicious circle as companies charge more for goods in order to pay for increased staffing costs. Again, this hasn’t transpired, despite strong employment figures.

“It turns out wage inflation peaked in spring at around 5.6%,” Gidopoulos added.

2. The ‘natural rate of interest’ falls over the long term

Many commentators claim the era of low inflation and interest rates is behind us, but Gidopoulos called this a “rather eccentric prediction”.

“Some of those who espouse this vision have a habit of avoiding analysis of first principles (‘interest rates were higher in the 20th century’ is not first-principles analysis),” he explained.

The analyst said he has heard quantitative easing (QE) described as a “silly experiment gone wrong” because it led to inflation a decade later.

Yet he pointed out there was no inflation for the first 10 or so years of QE. It wasn’t until the coronavirus pandemic, associated supply shocks and the biggest fiscal stimulus in history (per capita) that prices shot up.

“If the QE of 2010 to 2019 was keeping yields artificially low, there would have been an imbalance between savings and investments that would have caused inflation,” he explained. “But it didn’t. So there is no reason to believe that the cost of capital was artificially low in, for example, 2018 or 2019.”

Going further, he said that it is important to think of the natural rate of interest as a ‘magic number’ that prevents an imbalance: either when interest rates are so high that savings yield more than investments, causing deflation; or when interest rates are so low the imbalance is skewed in favour of excess investments, causing inflation.

“This ‘magic number’ is dynamic, and a function of the return environment of that economy,” he continued.

“In a dynamic, high GDP-growth economy, with a growing population and with productivity growth, the capital returns available to capital allocators would be so high that they would require a much higher natural rate of interest to counterbalance that inclination to allocate capital like crazy with a proportionate incentive to save.

“This was the macroeconomic environment of much of the 21st century, characterised by dynamic growth.”

However, Gidopoulos pointed out the past 30 years have seen slowing and structurally maturing GDP growth, an ageing population, sluggish or flat productivity growth, and a smaller impact from technological innovation.

This means the capital return environment is structurally more depressed than it has been in the past, and it takes a structurally lower natural rate of interest to balance savings against investments.

“The question for anyone who believes that the cost of capital will structurally trend up over the next five years is: what has changed about any of these macroeconomic fundamentals in the West?” the analyst added.

“I’m not a macroeconomist or a soothsayer, so not professing to know the answer: but there is quite the burden of proof on anyone espousing that this 30-year, textbook macroeconomic trend will reverse.”

3. The impact of interest rates also lags

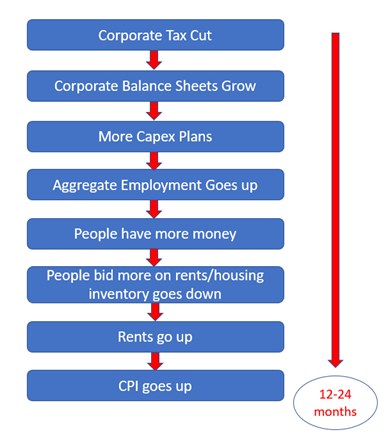

Gidopoulos said lags not only affect the reporting numbers of inflation, but inflation itself: any inflationary input has to pass through a number of steps before it affects CPI.

He pointed out the Covid period had many such inputs: expanded QE, fiscal spending policies, supply shocks, and so on.

“This also applies to monetary policy,” he continued, saying that if Step 1 in the above flow chart were ‘lower interest rates’, it would still hold.

“In the same way, the Federal Reserve has spent the last nine months or so raising interest rates (with most hikes concentrated in the last three months).

“It would be impossible for a rate hike that took place in, say, August, to make a dent on the economy by September. Rate hikes work in so many ways: by influencing corporate spending decisions, which in turn lead to lower employment and/or wages, and in turn lead to less consumer spending; by dampening consumer spending by increasing mortgage costs, which take time to roll over because most mortgages are not on variable rates; and so on.”

He added that with inflation turning lower in spite of the lagging mechanics, it is just as likely that the Federal Reserve overshoots with hikes on the way up as it did on the way down.

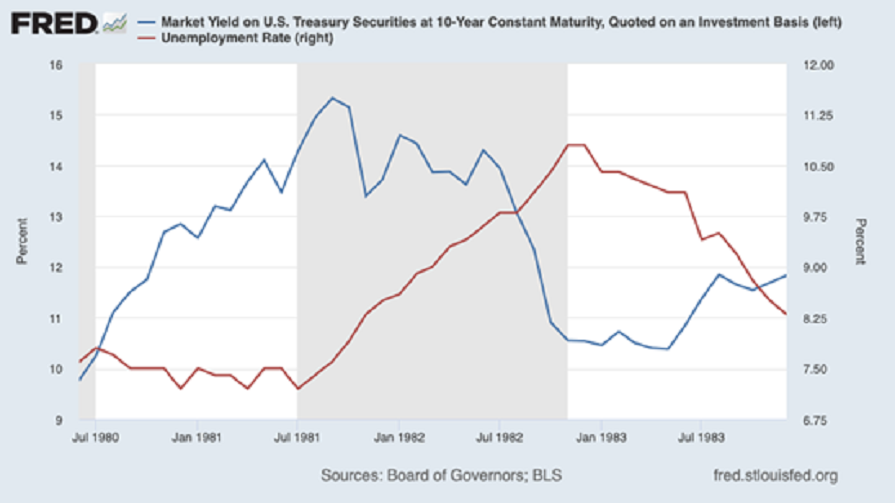

The last time the Federal Reserve embarked on a similar rate-hiking campaign to cool the economy was in the early 1980s. In 12 months of yields rising from 1980 to 1981, there was no movement in the unemployment rate until the following year.

In conclusion, Gidopoulos said that after the sharpest correction in valuations in his lifetime, a much higher cost of capital and a 2023 recession are largely priced into most equities.

“It is an unfortunate fact that quality growth has underperformed in such an aggressively quick rate-hiking environment,” he added.

“But it is at least the case that the balance of risk has moved away from cost of capital and towards earnings, and in such an environment we expect quality growth stocks to outperform more recession-sensitive, cost-sensitive stocks in the first phase of this recession and most likely to continue to outperform in the recovery phase.

“Here, the cost of capital must revert back to its ‘natural rate’ which, in today’s world of ageing demographics and maturing growth, is low.”