Central banks risk “killing the economy” by continuing to raise rates, but investors would be “foolish” to think they will stop, according to fund managers who have warned that they are investing “blind” at the moment.

Monetary policy and rising interest rates have been at the centre of investors’ minds lately, with predictions ranging from the notion that inflation will fall and central banks will cut rates before the end of the year, to stubborn prices and more hikes to come.

If the latter is true and central banks continue on their current path, Jacob de Tusch-Lec, co-manager of the Artemis Global Income fund, warned that they could “kill the economy”.

“We’re all moving ahead blind right now. Central banks are raising rates hoping that is going to dampen inflation. They're smarter than I am, but I can't really see why raising rates should create more labour,” he said.

The Federal Reserve and others are attempting to lower inflation without creating a global recession. So far, there have been severe re-ratings in “bubbles” such as the housing sector, cryptocurrencies and software stocks, with recession predicted at some point this year.

“It's like trying to put toothpaste back into tubes when they've been squirting that toothpaste out. They've been printing money, creating a lot of imbalances in the economy and it's not obvious to me that you can just raise rates and therefore get inflation down. What you can do is you can kill the economy. And ultimately, that is what's going to happen if they continue,” he said.

Tom Wells, manager of the Sanlam International Inflation Linked Bond fund, said that consumer resilience will drive rates beyond 6%, but that the economy won’t “die” for it, disagreeing with de Tusch-Lec.

“Investors would be foolish to think the Fed will divert from its objective to return inflation to target,” he said.

“In order to deliver inflation at 2% in the forecast period the Fed must choke consumer demand, which in itself will slow the economy, but if the consumer holds up then the Fed will be able to continue tightening policy beyond 5%, perhaps beyond 6%.”

According to Wells, the economy and its members will adapt and develop new strategies to prosper in a new paradigm – there’s another idea, however, which has no future.

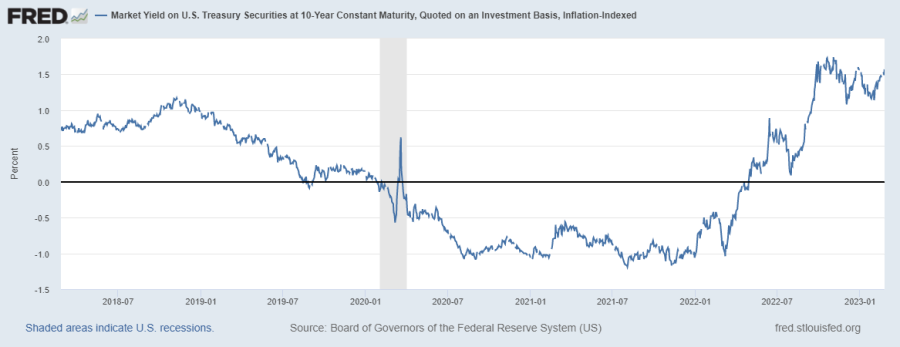

“The idea of killing an economy reminds me of headlines around the breakout of Covid, the economy didn’t die then and I don’t think it will now. In a world of many uncertainties one idea is certainly dead - TINA (there is no alternative). There IS a very credible alternative now, risk-free bonds paying investors a real yield to maturity of 1.5%,” he concluded.

Richard de Lisle, manager of the VT De Lisle America fund, was more sympathetic towards central banks' plight.

“These current policies were demonstrated beautifully by Paul Volcker in the early 80s: he raised interest rates well above the inflation rate until few dared borrow at all. The result was a whacking great recession in 1982,” he said.

“The mechanism clearly works best if businesses have borrowed heavily as they start to panic and shed staff, which is where we are at today. Raising rates creates more labour as businesses cut back.”

The other effect of raising rates is that of “dampening the spirit of the restless workers who think they won’t get out of bed for less than $20 an hour,” the manager continued.

“Once Starbucks stops building units on every corner as quickly as possible, the $20-an-hour baristas become less powerful. The cost of labour is reduced, the demand for goods is reduced. Being now jobless and back in bed, the baristas are not bidding up the price of stuff by spending money. Thus demand-pull inflation is also reduced.”

That’s how De Lisle said the situation should work in theory. But the debate is around an inflation that is exogenous, created by supply chains failing, de-globalisation, tariffs, commodity price rises and “general cantankerousness”, in which case “interest rate rises have but a mild and indirect effect,” he said.

Another part of monetary policy has been quantitative easing, which, according to the manager, only meant “squirting the toothpaste” if businesses took up the opportunity to increase production. This has only happened in speculative assets such as crypto and non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

“That pile of toothpaste has mainly been cleaned up in the last year and more will take place. Excess liquidity can now earn a risk-free return in short-term bonds and so all the hopeful speculations now have to justify their promise,” he said.

“As to all the debt created, a decade of decent inflation will do wonders to erode it to more sensible levels in real terms.”