Investing in emerging markets has lost much of its meaning as people seem to have forgotten the central proposition of the asset class – capturing the exponential growth of countries that are in development.

This means that investors are bypassing countries whose economies are growing 10% a year as they undergo changes as profound as the fall of the Berlin wall, according to Dominic Bokor-Ingram, FE fundinfo Alpha Manager of the Fiera Oaks EM Select fund.

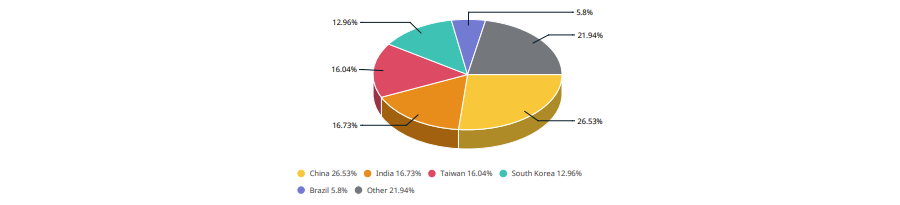

Bokor-Ingram does not invest in the largest countries in the MSCI Emerging Markets index (China, India, Taiwan, South Korea and Brazil). Instead, he looks elsewhere to find “the biggest alpha opportunities and the biggest mispricings”.

“There are 78 emerging countries with a stock market and people only invest in the largest. That’s why we focus our resources on the countries and the opportunities that other people aren't looking at,” he said.

Country weightings in the MSCI Emerging Markets index

Source: MSCI

Instead, Bokor-Ingram’s largest allocations are in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Greece, Vietnam – with the manager particularly excited about the opportunities in the Middle East and Saudi Arabia.

“What is happening in the Middle East now is probably the biggest social, cultural and economic change that I've seen in my career since the fall of the Berlin Wall,” he said.

“In Saudi Arabia six years ago women couldn't drive, today there are women Uber drivers; cinemas weren’t allowed, today there are 43 complexes in the country; men and women were not allowed to eat in the same restaurants and families didn't use to go out for entertainment, today there's a massive entertainment industry.”

“All this is creating a very strong growth, which is key. Saudi Arabia’s but also Abu Dhabi’s non-oil economies grew by 10% last year. That's the growth rate that China had in the 1990s.”

While not advocating for or against emerging markets, the manager took issue with the way the benchmarks and indices are put together.

“Emerging markets are a disparate asset class that has been put together by index providers. Within that, there obviously are some very exciting opportunities as well as places that you want to avoid. But our goal is to make absolute returns, not looking at benchmarks and make relative performance,” he said.

“Emerging markets funds might take positions that go a few points over or under the benchmark, but 90% of them end up tracking within a few percent of the index. That doesn't make any sense because so many countries are so different.”

For example, within the emerging label are countries that import commodities and oil but also those that export them. If the oil price is $20, China will do very well, but if the oil price is $150, China is going to be destroyed, while Saudi Arabia, Brazil and Mexico will do very well.

“If you're buying an emerging market index, you're just adhering to this categorization that emerging markets is anything that we don't classify as developed, rather than trying saying: How are we actually going to make money out of this opportunity set?,” said Bokor-Ingram.

Of the major emerging markets, the manager was most positive on China.

“Countries such as Korea and Taiwan are developed markets, but China has still got some way to go in terms of emerging. People are getting a bit carried away with China at the moment and there's a lot of anti-Chinese rhetoric around, probably for political reasons, but it’s still the second-largest economy in the world growing strongly at 5.5%,” he said.

“Chinese population falling could be beneficial too, because the key for companies to make money is not the GDP number, but the GDP per capita, which represents the excess purchasing power. So GDP growth of 5.5% and zero population growth is the same as when it was 7.5% and 2% population growth.”