ISAs have become a key savings vehicle for millions of people in the UK, who rely on the tax-free vehicle to shelter their hard-earned cash.

But they are under threat from chancellor Rachel Reeves, who is reportedly considering lowering the cash ISA threshold for savers from £20,000 to as low as £4,000.

While this may seem like a tax-grab, the reasons are far more complex, according to fund managers, who this week told Trustnet that PEPs (the predecessors of the ISA) were designed to encourage people to invest in the domestic economy, but they have morphed into a catch-all tax shelter.

One reason for lowering the cash ISA allowance but maintaining the stocks and shares allowance, therefore, is to encourage more investment into UK companies.

So let’s look at how much dry powder is sat on the sidelines. On the face of it, stocks and shares are already more popular. Of the £726bn held in ISA accounts across the UK, the majority of the money is in the stocks and shares variety, with just shy of £300m in cash ISAs, according to the latest data from HMRC.

But cash ISAs are far more popular than that. Some 22.3 million adults hold an ISA with around 3.6 million holding both stocks and shares and cash accounts, 4.2 million using ISAs solely to invest and 14.4 million with a cash ISA only. In the financial year 2022-2023, some 63.2% of all money put into the tax wrapper was parked in cash ISAs.

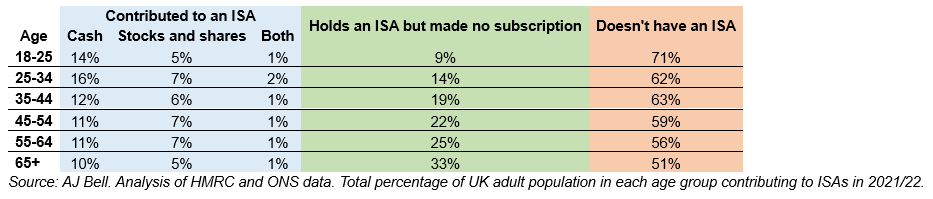

Savers are also twice as likely to put money into their cash ISA as they are their stocks and shares vehicle, according to data from AJ Bell, as the below table shows.

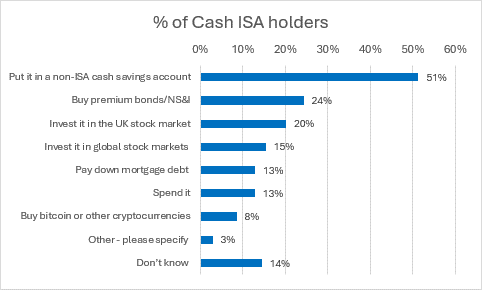

So will savers reallocate their cash if the allowance is slashed? AJ Bell asked its customers if they would be more inclined to invest if the cash ISA allowance was reduced. The resounding answer was no, with some 51% saying they would simply park their money in a taxable cash savings account, as the below chart shows.

Source: AJ Bell

Even those who would consider investing for the first time are by no means guaranteed to place it into UK businesses.

And for new investors, the most common advice for those starting out is to invest through a global equity tracker, which has a low weighting to the UK, meaning the impact would be minimal anyway.

So lowering the tax threshold may not necessarily have the impact fund managers want – to get the UK population backing British and buying domestic companies once again.

So what can be done?

If Reeves does come for cash ISAs – a potentially big decision considering the amount of savers it would hit – one option may be to introduce an inflation-adjusted cap on the total that can be held in a cash ISA.

Once it hits a certain amount, savers would no longer be able to add more in, although they would still be able to accrue money through their interest.

But cash ISAs are far from a catch-all solution. Also on the table include talks of removing stamp duty on UK shares – a measure that could encourage direct investment into UK companies but one that will require individuals to have some understanding of stocks.

Then there is the potential to mandate pension funds to put a percentage of their holdings into the UK.

This all comes on the heels of the failed Great British ISA – a much-discussed measure under the previous government to give people up to £5,000 to invest in UK companies. It hit far too many snags, including how to stop investors from putting money into global equity investment trusts and exchange-traded funds, which are listed as UK equities but still invest only a small portion in domestic names.

It is clearly an area of priority to get the UK market moving and encourage people to put their cash into domestic businesses.

But there is clearly no guarantee the government can get the population to invest with one measure alone. It will take a huge shift to change the cautious mentality of the public.