More than 20 years after the dotcom bubble burst, the impact of the crash continues to be felt by those who witnessed it first-hand. Names such as lastminute.com, Marconi Communications and Telewest still send shivers down the spine of investors who felt they had found a way to get rich quick without having to waste time studying such trivial matters as sales, profits or debt.

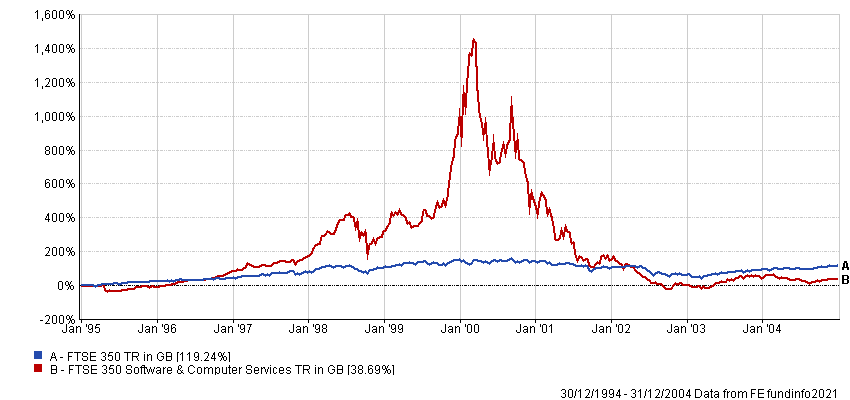

Performance of indices 01/01/1995 - 31/12/2004

Source: FE Analytics

It could even be argued that the dotcom bubble caused UK investors to become overly cautious: many fund managers maintained a sense of scepticism towards the tech stocks responsible for much of world growth over the past decade, warning it would only be a matter of time before value investing reasserted itself, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Yet while investors haven’t forgotten the lessons of the dotcom bubble when looking at tech, Dr Paul Jourdan, manager of the TB Amati UK Smaller Companies fund, warned they seem to have trouble applying them to another sector: biotech. He said what makes this is all the more bizarre is that much of the blame for the dotcom bubble could be placed at the feet of one biotech company: British Biotech.

“In 1986 in Oxford, a scientist [Keith McCullagh] set up his own biotechnology company,” Jourdan began.

“A few years later its scientists were fiddling around with compounds in the lab and found one that seemed to fight every cancer they tried it on, and he got very excited about this.

“He wanted to embark on Phase I trials, then realised he needed a heck of a lot of money for that and the only place he could get it was the stock market.”

Back then in 1992, companies were not allowed to list on the FTSE unless they were profitable and had a product to sell.

Although British Biotech had neither of these, it managed to get the rules changed so it could float.

“Think about how significant that was: the whole of the dotcom boom probably couldn’t have happened if it hadn't got that rule changed,” Jourdan continued, “because it was all about floating companies that had made no profits.”

The drug, Marimastat, passed Phase I and II trials, at which point the company wrote a press release hailing this as proof it worked. The press responded in a predictable manner, hailing the wonder UK biotech company that had found a cure for cancer, and the market cap of British Biotech eventually hit £2.5bn.

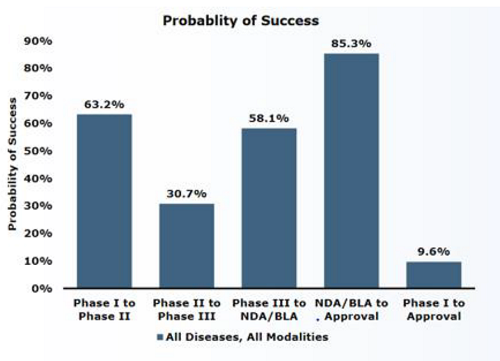

But it was here the problems began. Jourdan said a common mistake among novice investors in biotech is underestimating how high the odds are stacked against a drug making it from concept to approval.

About 63 per cent of drugs make it past Phase I, which evaluates their safety; 31 per cent make it past Phase II, which evaluates if they work or not; and 58 per cent make it past Phase III, at which point they can be presented to the regulator. Even then though, there is only an 85 per cent chance they will receive approval. Together, this means the chance of a drug being approved for use from the point it first enters trials is just 9.6 per cent.

Source: BIO Industry, “Clinical Development Success Rates 2006-2015”

Jourdan said that in the case of British Biotech, it was Phase III where it came unstuck.

“The chief scientist Dr Andrew Millar got a phone call one evening from a doctor doing the Phase III trial saying one of the patients had developed a heart condition,” the manager added.

“Dr Millar panicked and thought, ‘what happens if this drug causes a heart condition?’, so he decided to look at the data. That is called ‘unblinding’, which is regarded as unethical in a drug trial where it is supposed to remain sealed until the end.

“He went back to the chief executive and said, ‘we've got a problem here, the drug doesn't work’. The chief executive threw him out: he didn't want to know the bad news.”

Shortly afterwards, Phase III trial data was published showing Marimastat didn’t work, British Biotech's share price plummeted and a parliamentary inquiry was set up into the episode.

Yet this is not the end of the story and although investors in British Biotech lost a lot of money, Jourdan described it as “peanuts” compared with the amount lost by the company that took it over: Vernalis.

“You would think we would learn our lessons as investors, but one of the great beauties of the biotech sector is that optimism is indefatigable and inextinguishable,” the manager said.

He added that while Vernalis had a team of research scientists in Cambridge who were regarded as among the brightest in the world, with five drugs in clinical trials, the company never made a penny.

The final episode saw the company give up on revolutionary drugs that never went anywhere and focus instead on a money spinner that would be easy to get approved. It settled on a cough syrup.

“This was codeine plus some fancy drug where it was already on the market, but it thought, ‘we can make a 12-hour version of this, we can re-patent it, it will hardly cost anything,” Jourdan said.

“Vernalis reached a deal with another company that specialised in this stuff and paid it about $25m, then it got the thing approved.

“But this is another easy thing to forget in biotech investing: once you've got your product approved, you need to become a completely different kind of company because you've actually got to sell it.

“The problem then was, it was just another cough/cold mixture, and it wanted $100 for it because it lasted 12 hours. It turned out nobody wanted to pay that much, even in America.

“Vernalis got sold for $43m in 2018 and when it finally went, the cumulative losses on its balance sheet were £760m.”

Jourdan said the story of British Biotech and Vernalis is just the tip of the iceberg and it is not only investors who can get burnt – he pointed to the example of NeuTec, acquired by Novartis for $570m in 2006, but subsequently written off four years later after its drug Mycograb failed to make it past the regulator.

This is the reason Amati hired specialist Dr Gareth Blades, who has a background in spinning out biotech companies and has a rigid discipline when investing in this sector.

“One of the things we look for is how vetted the ideas and principles are,” said Blades. “An example of companies that have done a good job of this are ones like Renalytix AI which have been spun out of Mount Sinai, a hospital network based in New York, but are listing on AIM.

“Their core idea is based on sometimes a decade's worth of academic research, they're not talking about something esoteric, all of these ideas have been tried in real-world clinics. They have a proof of concept behind them and you can point to several hundred patients having a tangible benefit because of these interventions.”

Jourdan added: “One of my struggles with this sector has always been I'm not a scientist, so I know I'm only ever scratching the surface of the science and dealing with analogies. That's really why we have someone like Gareth.”

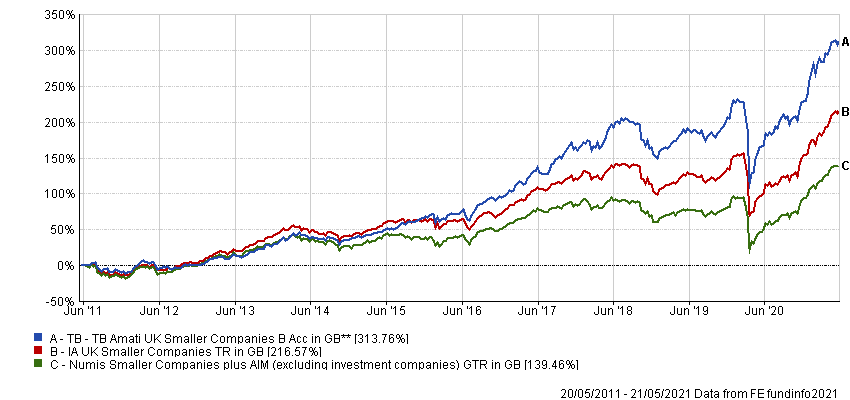

Data from FE Analytics shows TB Amati UK Smaller Companies has made 313.76 per cent over the past 10 years, compared with 216.57 per cent from the IA UK Smaller Companies sector and 139.46 per cent from the Numis Smaller Companies plus AIM index.

Performance of fund vs sector and index over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

The £943m fund has ongoing charges of 0.89 per cent.