The crash of March 2020 created an enormous buying opportunity for investors with a strong stomach for risk, and many of the best prospects were to be found in the securities that had fallen the most in the initial sell-off.

One prime example was Ocean Dial’s India Capital Growth trust, which bottomed out in April last year 72.12 per cent below its pre-coronavirus peak.

Performance of trust from peak to trough

Source: FE Analytics

In May 2020, even after a significant bounce from this low point, chief investment officer and portfolio manager David Cornell told Trustnet the sell-off had been overdone and that if his holdings simply returned to fair value, his trust would make 40 per cent.

However, the rebound exceeded even these lofty expectations and the trust is up 115.54 per cent since the date of the interview, and more than 200 per cent since the bottom of the market.

But surely if a 40 per cent rally returned his holdings to fair value, a gain of almost three times that level would make them expensive? This is a point Cornell doesn’t attempt to dispute.

Performance of trust from trough to peak

Source: FE Analytics

“Valuations are not cheap by historical standards, India's trading about one standard deviation above its long-term average on a forward P/E basis,” he warned, before adding: “But I don't think that's the right way to look at it.

“Of course, I would say that. But the hole we just filled comes from a major correction that happened three or four years ago that was then compounded by the pandemic.

“We think it's going to deliver 15 per cent earnings growth [annualised] over the next four or five years in sterling terms.

“We don't think the changes that have happened in India are reflected in valuations: to some extent Covid has fast-tracked them, but to some extent it has masked them.”

Every country experienced an acceleration of digitalisation during the pandemic, but Cornell believes India has benefited more than most from the move online. He said India’s economy has long been hampered by corruption, but digitalisation has helped the transition from what he referred to as a patronage-based system of doing business to a rules-based one, by removing the opportunity to give or receive bribes.

As an example, the chief investment officer pointed out how difficult it used to be to open a business in India.

“Historically, you would lobby the state government for the permissions you needed to get access to the land or to build the road,” he said. “And that would require several meetings in the state government where the middle-ranking bureaucrat would use his influence to delay the proceedings to such an extent that a brown paper parcel would have to be moved under the table for the application to be fast-tracked.

“Now that all happens online, there's no meeting. The application process is filled in online by the company wishing to acquire permission and the state government has to respond to that within a certain timeframe, so you can see how the process is changing.

He added: “All social security payments are now paid by the government directly into individual bank accounts, whereas historically they would be paid in a physical format like a bag of rice, fertiliser or cooking fuel. The ability of the middle-ranking bureaucrat to facilitate that process in return for cash is no longer possible.”

The digitalisation of India is a relatively recent phenomenon, coinciding with the availability of reasonably priced smartphones: there are now 763 million handsets in the country, which are responsible for 99 per cent of all internet activity. As Cornell noted, India completely bypassed the laptop and desktop stages.

But digitalisation is not the only major theme helping India to tackle its inefficiencies. Cornell pointed to prime minister Narendra Modi’s wide-reaching package of reforms which created much disruption when they were first introduced, but should act as a long-term tailwind for India’s economy and stock market.

These include demonetisation, the Goods and Services Tax (to solve the problem of large-scale tax evasion) and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, which Cornell likened to “lancing a boil”: it created a short-term liquidity crisis, but will allow the banking system to operate far more effectively in the long run.

When asked for hard evidence of the benefits of these reforms, Cornell replied: “I can think of a number of companies that have gone bust, and the families that owned them are in jail. That's pretty hard evidence.

“Historically, the banking system in India used to do what we call ‘extend and pretend’ and they call ‘evergreen’ – loans that went unpaid and were just rolled over and extended in perpetuity.

“The promoters of these businesses never had any intention of paying the loans back and the banks never had any intention of calling them.

“The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code has forced banks to be much more transparent. For example, if a loan to a big industrial company was syndicated across various banks, they would all have qualified it in a different way. Some would say it was a performing loan, some would say it was a non-performing loan.

“Now if a company doesn't pay the interest on the loan, all the banks have to record that as a non-performing asset.”

While these reforms are ongoing, Cornell said India appeared to have got past the “Big Bang” stage and was moving towards a more targeted approach towards individual sectors when the coronavirus hit. He said the pandemic masked a noticeable turnaround in growth and earnings.

Although he admitted the coronavirus is still a “frightening situation”, he said that once India has overcome the pandemic, it could be about to enter an exciting phase in its economic evolution, leading to a change in perception among foreign investors.

“We're going to have big internet stocks in the index, which is going to make it look a bit less like the UK, an old economy index, and a bit more like China, with the Baidus and the Tencents,” he added.

“I would think India's going to mirror the growth that China went through between 2012 and 2020. India is six or seven years behind China, so it is just about to enter that, but with an internet infrastructure that's already in place.

“We're in a holding period now and, if we get it right, we could make investors a huge amount of money over the next four years.”

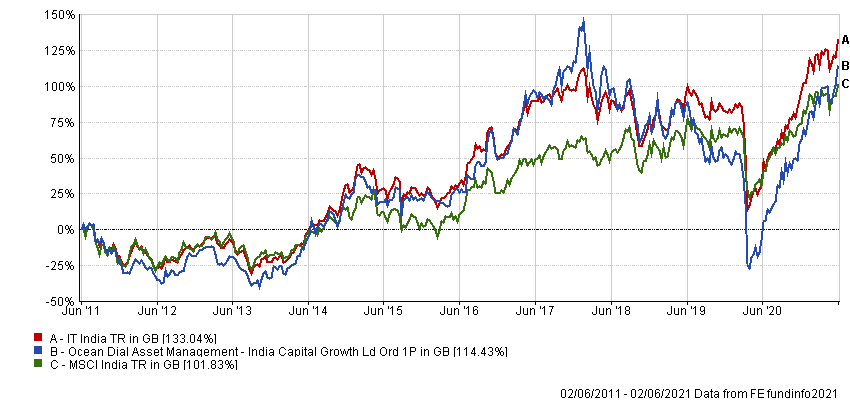

Data from FE Analytics shows India Capital Growth has made 114.43 per cent over the past 10 years, compared with gains of 133.04 per cent from the IT India sector and 101.83 per cent from the MSCI India index.

Performance of trust vs sector and index over 10yrs

Source: FE Analytics

The trust is on a discount of 12.49 per cent, compared with 17.34 and 16.89 per cent from its one- and three-year average.

It has ongoing charges of 0.5 per cent.