Large-cap companies have led global markets in recent years but their dominance could be coming to an end, according to Gervais Williams, manager of the Diverse Income Trust.

A decade of free cash has inflated the market capitalisation of the largest companies to unsustainable levels, meaning a sizable rebalance could be in store now that quantitative easing has ground to a halt.

“Quantitative easing really works by distorting market prices and manipulating the cost of debt, which in doing so has made it easier to borrow and driven up valuations,” Williams said. “Capital has been misallocated because prices are wrong, so you get a lack of productivity which hasn’t improved for the past 15 years.

“Effectively, quantitative easing leads to indexation. You can make a lot of money from these index funds but the more you put money into them, you just put more and more money into bigger and bigger companies.”

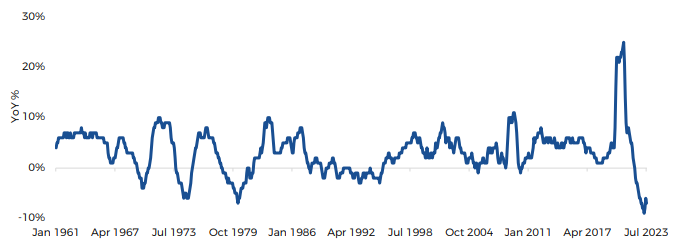

US gross domestic product since 1961

Source: Premier Miton

Now that central banks have “pulled the plug out the bottom of the bath” on quantitative easing following a burst in stimulus during the pandemic, Williams said “the nightmare” now facing investors is obsolescence risk.

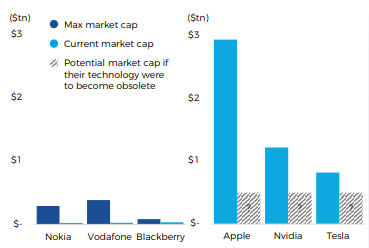

Mega-cap technology companies that account for much of the biggest indices could shrink massively just as previous giants such as Nokia, Vodaphone and Blackberry did in the past.

This is something Williams said could happen to companies such as Apple, Nvidia and Tesla now that sales and profit growth have slowed, with their enormous market capitalisations leaving them vulnerable to downside risk.

“The market is very poor at pricing obsolescence risk and you can be on the wrong side of this,” he added. “Clearly, if you run a capital appreciation strategy, there’s nothing to hold you on the way down.

“It’s been a pretty uncomfortable time and it could get more uncomfortable because the more you stress the system, the more something might change unexpectedly.”

Market cap expectations

Source: Premier Miton

The age of large-cap dominance may be coming to an end, but Williams said markets have been concerningly slow to react, with many investors refusing to let go to of the past.

“Groupthink tends to happen when you get a long-term trend which is very successful, very consistent and everyone buys in,” he explained. “You get to a stage where the theme becomes unquestioned.

“And it’s not just that people don’t question it, but you get this illusion of unanimity. This is really driven by people who have questions about this long-term trend – particularly if they’re new to the industry – but don’t want to put their hand up in a meeting full of experienced people and risk looking silly.”

Rather than acknowledging the changing environment, markets are clinging to the model that worked well in the past, which is largely being perpetuated by asset management firms themselves.

“Even when things do go off the rails and an event breaks the trend, you find there’s a lot of post rationalisation,” Williams added. “Investment groups often continue to hold these positions, even when there are foreseeable downside risks.”

These firms are deeply invested in the success of large-cap companies, but Williams expects they will be forced to acknowledge the shifting market landscape as further changes unfold.

He said: “We’re going to see a behaviour change in institutions that have been sucked into indexation. We think they’re going to be more open minded to investing across a wider range of companies.

“The problem with indices is they give the largest weightings to the largest companies and in doing so have very big concentration risks in your portfolio. If one of these big-caps falls from grace, it can end up costing a large amount.”

If large-caps struggle to maintain their dominant market positions, as Williams suggests, it could create an excellent environment for smaller companies to thrive.

The bloating size of giant companies has been “sucking money from other parts of the market, particularly further down the market-cap range,” but that capital could now be redirected to unloved smaller companies.

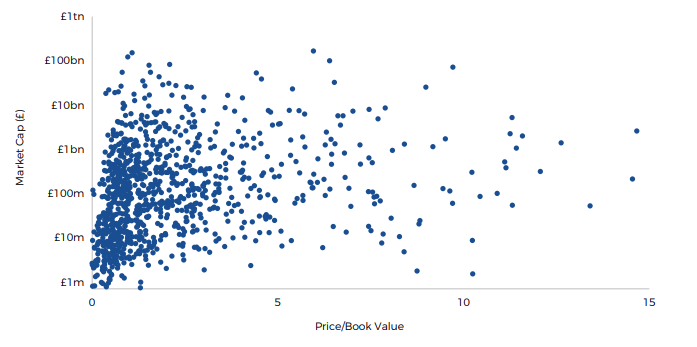

This could be especially beneficial for the UK, where more than half of all listed companies are below £1bn in market cap and are trading at low valuations.

UK listed stock valuations vs size

Source: Premier Miton

Williams said: “For the first time in 30 years, I think small-caps are going to not just outperform, but enjoy a super cycle of their own from the extraordinarily low valuations we’ve reached.

“When it comes to the UK market, we’ve been out of fashion. Hares have done extremely well and clients are absolutely loaded with them, but now we’ve got some uncertainty, tortoises may be the way forward.

Williams himself has invested almost a third (30%) of his £247m portfolio into FTSE AIM stocks, with an additional 20.3% held in FTSE Small Cap companies.