An 18th century gentleman or lady wouldn’t miss a beat if presented with an interest rate of 5.25%. From the Bank of England’s formation in 1694, interest rates have averaged 4.7%.

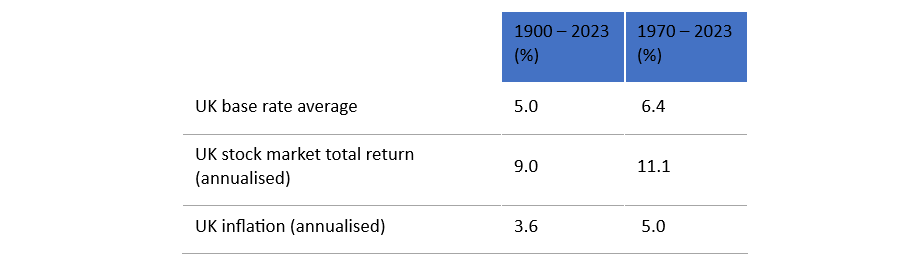

During periods in the modern era when rates have stood at this sort of level, inflation has often also ticked along at a reasonable clip. But shares of companies have generally posted real returns over sensible holding periods. Since 1900 and 1970 respectively, for instance, here are the numbers.

Source: Evenlode

The real ‘news’ in terms of the current interest rate environment is the rapidity of the rise. Last January, UK base rates were only 0.25%. This rapid change is not British exceptionalism, but part of a global trend. Rates in the US, for instance, have been on a very similar trajectory, with the federal funds rate now standing at 5.25% - 5.50%.

Less frothy

When interest rates are low, history has shown that pockets of financial markets can get frothy. As the economist and journalist Walter Bagehot noted in 1852, the archetypal Englishman John Bull ‘can stand a great deal, but he cannot stand 2%’.

When interest rates fall to such a low level, there is a danger that investors respond by taking greater risks. As Bagehot went on, ‘people won’t take 2%; they won’t bear a loss of income. Instead of that dreadful event, they invest their careful savings in something impossible – a canal to Kamchatka, a railway to Watchet, a plan for animating the Dead Sea, a corporation for shipping skates to the Torrid Zone. A century or two ago, the Dutch burgomasters, of all people in the world, invented the most imaginative occupation. They speculated in impossible tulips’.

There was no tulip bubble in the 2010s, but as rates have normalised over the past couple of years some glitches in the financial ‘matrix’ have emerged. Issues with cryptocurrencies, FTX, NFTs, Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse can all be loosely collected in this category. More generally, highly leveraged structures are significantly riskier when interest rates stand at 5.25% rather than 0.25%.

One can advance an argument that the removal of excess froth from the financial system has a cathartic, healthy dynamic. In the fullness of time, it should benefit sensibly run companies with sensible capital structures.

Modest valuations a comfort

More mundanely, the rise in interest rates has provided another option for savers, which has presented a headwind for equity valuations over recent months. There is now an alternative in the form of interest from cash or bond yields.

Within the UK stock market though, we are reassured by how modest valuations appear when viewed from the perspective of longer-term history. Not unrelated presumably, to how downbeat sentiment is towards the UK stock market (and has been, really, for the past few years).

Taking a specific example, consumer health and hygiene company Reckitt Benckiser has returned a cumulative 678% over the past 20 years, compared to 277% for the FTSE All Share. Its current year price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple is 17x compared to a P/E multiple of 18x 20 years ago (and an average P/E of 20x for the period as a whole).

And here’s another. Test and measurement company Spectris has returned 1,235% over the past 20 years, also compared to 277% for the FTSE All Share. But its current year P/E multiple is 17x compared to a P/E multiple of 20x 20 years ago (and an average P/E of 17x for the period as a whole).

Neither company is, of course, perfect (there is no such thing) but they both expect compound growth to continue over coming years. As Spectris management recently put it, ‘we expect to deliver organic growth consistent with our medium-term objectives of 6-7%, alongside strong progress on expanding margins, as we drive forward with our ambitions to be a leading sustainable business’.

Though these are nice examples, there are many holdings in the Evenlode Income fund for which valuation has either subtracted from, or not meaningfully added, to the attractive long-term compound returns generated by fundamental growth and dividends alone. The use of patience and fortitude in the act of capturing these long-run fundamental returns sums up the ‘get rich slowly’ approach.

As the investor Peter Lynch once put it, ‘often, there is no correlation between the success of a company's operations and the success of its stock over a few months or even a few years. In the long term, there is a 100% correlation between the success of the company and the success of its stock. This disparity is the key to making money; it pays to be patient, and to own successful companies’.

Hugh Yarrow is a fund manager at Evenlode Investment. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.